A slave in 1850 didn't have many choices in life. He could stay on his master's plantation, resigning himself to a life of hard labor, often brutal physical punishment and possibly a broken family as he watched his loved ones be sold away. Not all slaves had the same life, but this was what he might expect if he remained in bondage.

Or he could run away.

Advertisement

Escaping was a very uncertain prospect. The master would either hunt the slave himself or send brutal slave hunters to track him down. If caught, not only did the runaway face almost certain death, but the rest of the slaves on his plantation were often witness to his execution and were punished themselves.

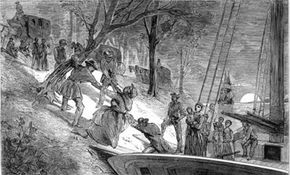

And life on the run was difficult, to say the least. The fugitive had to be wary of everyone -- strangers could recognize him as a slave and turn him in, and other slaves could rat him out to curry favor with their masters. He would have to travel at night, following the North Star when the weather was clear and sleeping in hay lofts and caves during the day. He might get some help from people along the way, but anyone who was kind to him was also suspect.

If the runaway did make it to a Northern state, there were still perils. Plenty of people, white and black, wanted the reward money they could receive for turning him in, and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 (which was made even harsher in 1850) meant that if his master could find him, he could bring his "property" back South as a slave again -- if the master didn't kill him, that is. So a runaway's best hope was to get to Canada.

With all the danger, there was little chance of success. But if he did make it ... freedom.

The word was too much for many slaves even to contemplate, much less attempt. But according to at least one estimate, during the 1800s, more than 100,000 slaves would take their chances to start a new life. The Underground Railroad was their ticket to freedom [source: Freedom Center].

Advertisement