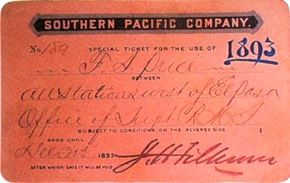

By 1900, America's railroads were very nearly at their peak, both in terms of overall mileage and employment. In the 20 years leading up to World War I, however, the foundations of railroading would change drastically. New technology would be introduced, and the nation would go to war, during which time the railroads would be run by the government. Most significantly, the railroads would enter the age of government regulation.

The dawn of the twentieth century was, for the most part, eagerly anticipated by America. There was much to celebrate. Things were going well for business, and that meant there was employment for almost everyone.

Advertisement

Railroads capitalized on the prosperity with colorful brochures promoting top-notch passenger trains. The West was glorified as the nation's wonderland, regularly being featured in railroad-commissioned paintings and in the pages of numerous magazines. Posters featuring dreamy damsels lured vacationers to exotic destinations like California, while fast "Limiteds" raced business travelers across the land.

The nation's railroads were still growing. By 1900, more than 195,000 miles of track were in service, and there were still another 16 years of expansion ahead. The biggest opportunities existed in the West and in the South, where large portions of the landscape were still lightly populated.

During the years preceding World War I, the Florida East Coast Railroad extended its rails all the way to Key West; the Union Pacific reached Los Angeles by crossing through the Utah, Nevada, and California deserts; the Western Pacific completed its line from Salt Lake City to Oakland, California; and the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific linked the Midwest to the West Coast.

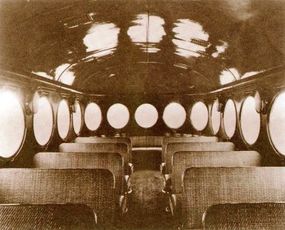

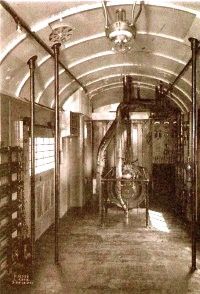

It was around this time that the passenger train achieved levels of dependability, comfort, and speed that rail passengers would generally enjoy for the next 50 to 60 years. Trains became so reliable as to encourage entire generations of business travelers to schedule meetings in distant cities the next day, and the basic amenities of train travel -- a comfortable lounge, impeccable dining car service, sleeping cars with restrooms and running water, and carpets throughout -- were here to stay. Railroads even began to regularly operate their finer trains at speeds that even today's travelers would consider "fast" -- 80 to 100 miles per hour.

Advertisement