Key Takeaways

- The California Gold Rush of the mid-19th century was a pivotal event that attracted people from around the world to seek their fortunes in the goldfields.

- The discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill in 1848 sparked a massive influx of prospectors, leading to rapid population growth and profound social and economic changes in California.

- While only a small percentage of prospectors struck it rich, the Gold Rush left a lasting legacy on American history, shaping the development of the West and fueling dreams of wealth and opportunity.

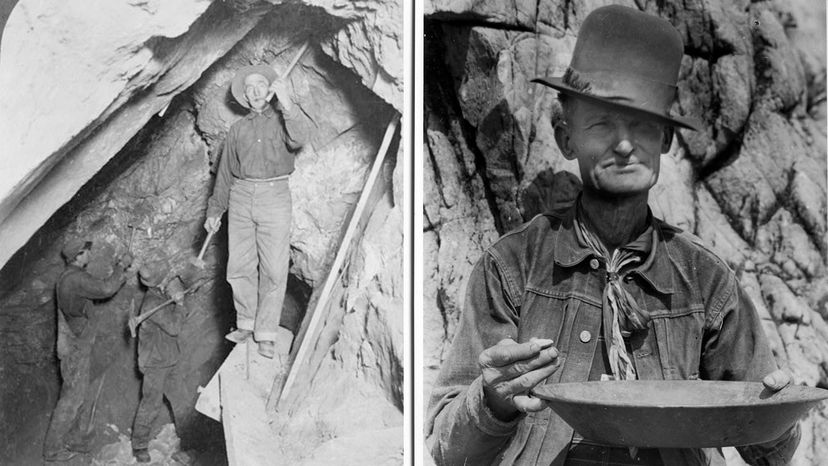

You'd think that finding gold on your property would mean the end of all your troubles. But for John Sutter, it was just about the worst thing that could have happened. In the 19th century, Sutter was an entrepreneur and owner of a large tract of land in Coloma, California. He hired a carpenter named James Marshall to build a water wheel for a mill on his property. Then in 1848, Marshall discovered flakes of gold in the river.

Although the two men tried to keep the find a secret, they failed miserably. The news spread like a modern California wildfire. Especially after an enterprising gentleman named Sam Brannan paraded around carrying a vial of gold and announcing the whereabouts of the new discovery. He himself didn't go prospecting. He knew of a smarter way to make his fortune, as we shall see.

Advertisement

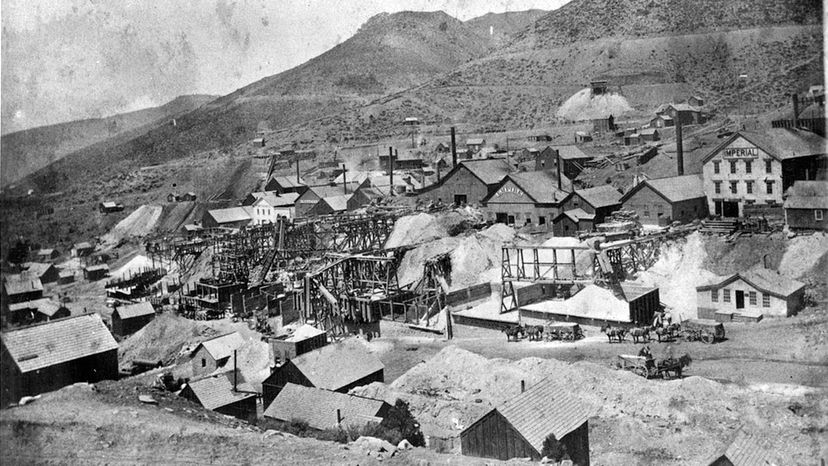

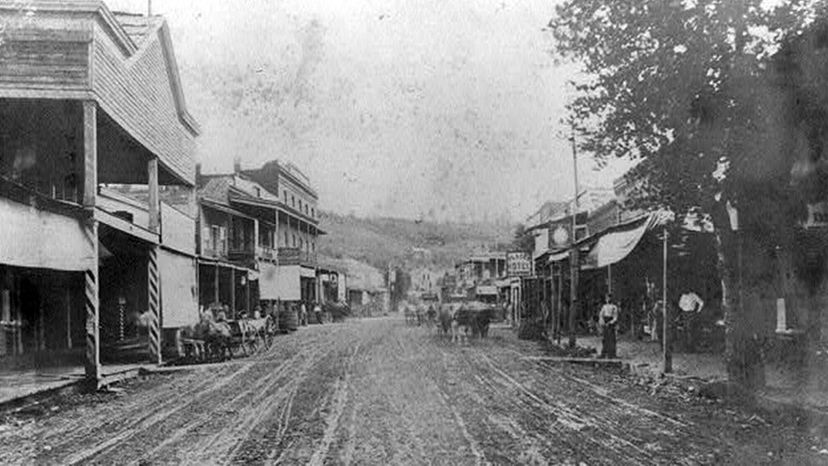

In just four years — by 1852 — Sutter would be bankrupt, his property overrun and his livestock stolen by avaricious prospectors. It's hard to exaggerate the enormity of the gold rush's demographic impact on California. In a few short years, it transformed from a sparsely populated, newly acquired territory of the U.S. to a fully formed state with a thriving economy. Between 1848 and 1849, the influx of settlers exploded from just 400 to 90,000.

Advertisement