If you're a fan of classic 1960s music, you probably know Edwin Starr's 1970 hit "War," with its memorable refrain, "What is it good for? Absolutely nothing."

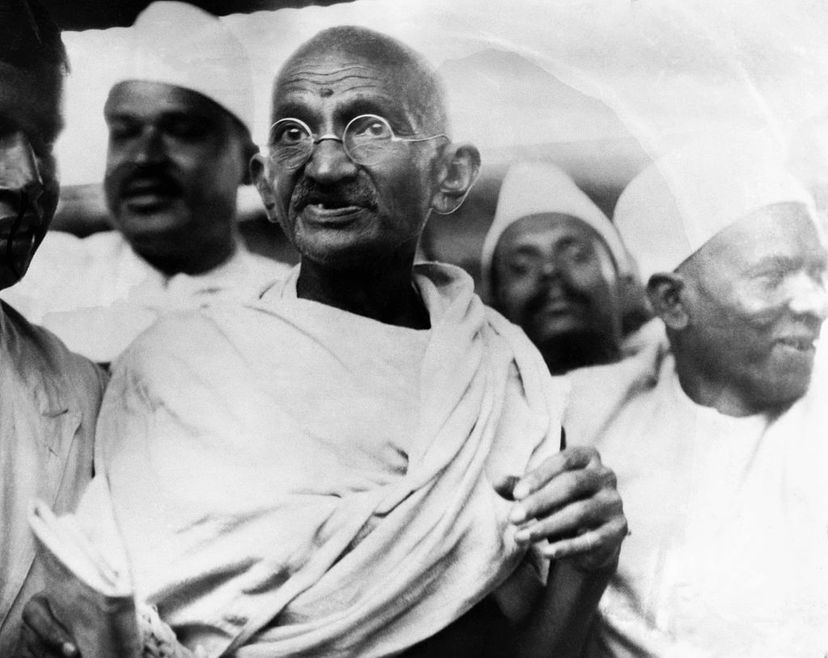

That's an idea that resonates with people who embrace the philosophy of pacifism — in a general sense, the opposition to violence and war as a means of settling disputes.

Advertisement

Throughout history, those with pacifist beliefs have rejected the use of force, and advocated other ways to resolve differences. The term comes from the Latin word pacificus, which means "peace-making" [source: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy].

For some pacifists, that means refusing to take up arms in the military, even at the risk of being punished for it. In Israel, for example, a young man named Nathan Blanc made headlines in 2013 for repeatedly refusing to serve during the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in Gaza, even though it meant spending more than 100 days in military prison.

Blanc told the Guardian, a British newspaper, that he felt both sides were in the wrong, and more killing would only deepen the fight. "We, as citizens and human beings, have a moral duty to refuse to participate in this cynical game," he said in the article [source: Sherwood].

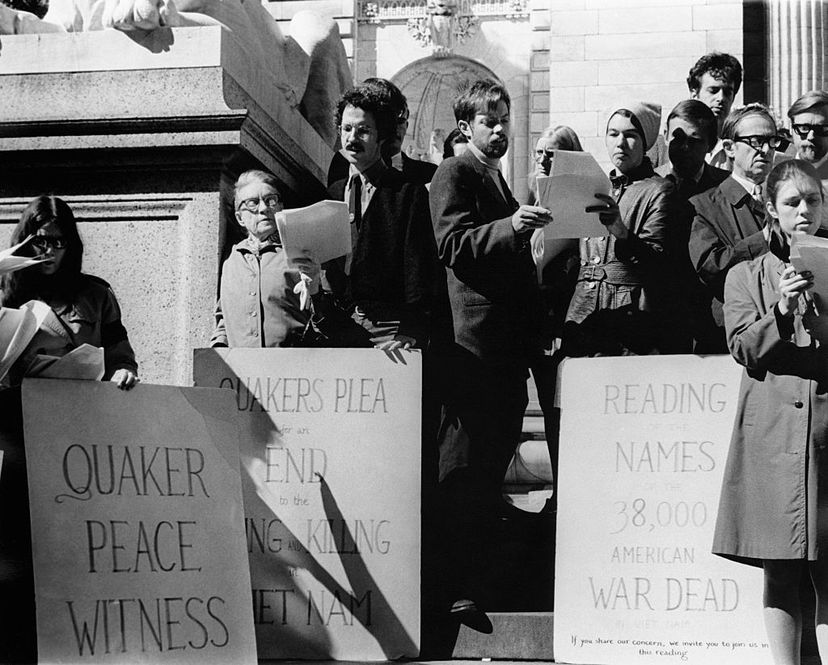

Blanc joined a pacifist tradition that dates back to ancient times, and in the modern era includes activists who've used nonviolent methods — such as sit-ins, boycotts and protest marches — to challenge what they think is wrong.

To some, pacifism might seem dreamily impractical and dangerous, not to mention possibly unpatriotic. But proponents argue that pacifism —particularly in its more moderate, flexible variations — actually is a useful way of dealing with conflict, and one that's a better fit with basic human nature.

Duane L. Cady, a former philosophy professor at Hamline College in Minnesota and author of the book "Warism to Pacifism: A Moral Continuum," has written that once a person refuses to take for granted that force is the most effective solution, pacifism is not naïve and unrealistic at all. In fact, all of us are pacifists to some degree, since all of us oppose violence as a means of interaction in many aspects of our lives."

In this article, we'll look at the different types of pacifism, the history of pacifist beliefs and how pacifism has evolved in the age of terrorism.

Advertisement