The term "Machiavellian" points to Niccoló Machiavelli, a Florentine philosopher and diplomat who lived during the Renaissance and wrote "The Prince." Machiavelli's last name has been invoked with such regularity that it's become synonymous with double-dealing, unscrupulous, treacherous, scheming and deceitful traits.

"A prince never lacks good reasons to break his promises," Machiavelli wrote in the 1532 treatise. Along with other infamous quotes from Machiavelli's book, the saying underscores the benefits of manipulative tendencies — especially for leaders.

Advertisement

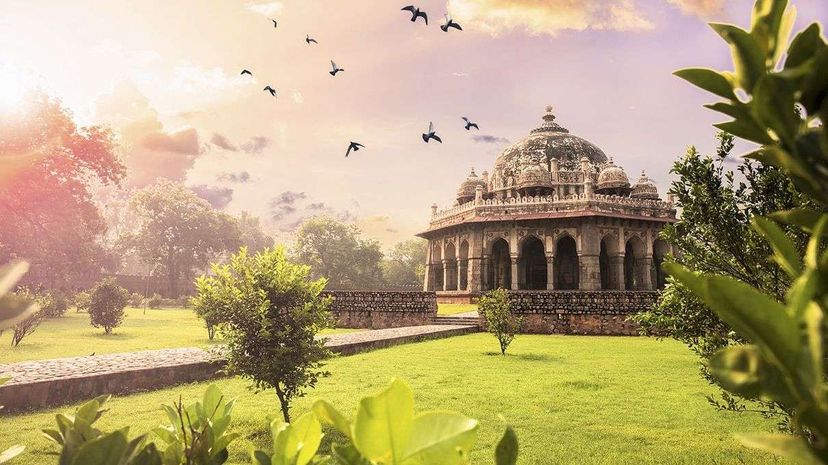

Before we get too Machiavellian, however, perhaps we should give credit where credit is due, and turn our attention to the Indian subcontinent and its ancient works — namely, a handbook for despots written long before Machiavelli was born. The "Arthashastra" is basically an empire-running guidebook with detailed information about ruling a kingdom that predated Machiavelli by about 1,800 years. From military tactics, diplomacy and law to spycraft, taxation and prison maintenance, the "Arthashastra" took a no-nonsense, unflinching approach to ruling with a firm hand.

The "Arthashastra" was likely composed by a number of authors, but is most often attributed to a man named Kautilya (approximately 350-275 B.C.E.). He was an advisor to Chandragupta, the first ruler of the Mauryan Empire. This Iron Age empire covered a vast portion of Northern India and represented the continent's first complex ruling society. The word "Arthashastra" is Sanskrit, which can be notoriously tough to translate into modern day vocab, but most experts agree the book's English title is the equivalent of "The Science of Material Gain."

Cataloging helpful information about setting up a ring of spies doesn't seem too dastardly, but Kautilya's advice didn't stop there. He also covered the "how to" aspects of assassinations and delved into the necessity of murdering family members to gain or retain power.

But not all his advice encouraged aspiring leaders to take a walk on the dark side. Kautilya outlined the ideal schedule for a dedicated ruler, which involved hearing reports from various underlings at sunrise, followed by a public forum, a meeting with ministers, correspondence and more. Additionally, Kautilya recommended a ruler be given fewer than five hours in which to sleep. (No rest for the wicked, it seems.) He also advocated for peaceful foreign policy and international neutrality, and took a deep dive into the organization of government administration.

Like Kautilya, Machiavelli's political musings weren't wholly dark hearted and heavy handed. Much of "The Prince" was, in fact, a nuanced and noble take on leadership. Machiavelli may be remembered for writing "the ends justify the means," but the phrase actually doesn't appear in the book. Instead, Machiavelli's tempered take on the topic was "let a prince have the credit of conquering and holding his state, the means will always be considered honest and he will be praised by everybody because the vulgar are always taken by what a thing seems to be and by what comes of it."

So why do we say "Machiavellian" instead of "Kautilyan" to describe someone's ruthless actions, and assign high-school students "The Prince" instead of the "Arthashastra"? While Machiavelli's work on governance influenced much of European history and those with a Eurocentric worldview for centuries, Kautilya's lesser-known work was nearly lost to history. It wasn't until 1905 that a version of the book was discovered. Inscribed on palm leaves, the discovery was a rewriting made about 600 years ago, and copied a copy of the original manuscript. The discovery was written in Sanskrit, and was the first manuscript to be recovered in hundreds of years.

"Arthashastra ... significantly altered our understanding of ancient India," H.P. Devaki, director of the Oriential Research Institute, told Outlook India on the centenary of the tome's modern republication in 1909. "A lot of course correction happened in history after this was published. And since it touched upon subjects like law, politics, economics, trade, governance, diplomacy, war, weaponry, natural calamities, the vices and virtues of rulers, it also naturally attracted a lot of general interest."

Kautilya may not be a household name, but his legacy is still evident. "Arthashastra" is a must-read for those studying diplomacy in India, and several of the country's universities and diplomatic offices bear Kautilya's name.

Advertisement