It's impossible to trace the origin of the first American flag to one specific person or event. The familiar 13 stripes with 13 stars over a blue field (known as a canton) in the upper left evolved from naval flags, colonial flags, and various flags of protest and rebellion used by colonists as their anger toward England grew in the years before the Revolutionary War.

Among the many American revolutionary flags were the Washington Squadron (a white flag with a green pine tree), the Gadsden flag (a yellow flag with a rattlesnake and the words "Don't tread on me,") and the Sons of Liberty (a flag with nine vertical stripes of red and white) [sources: Teachout, Homer].

The need for a single flag was recognized as tensions and violence flared at the start of the Revolutionary War. The small American Navy needed its own flag so it wouldn't accidentally be fired upon by allies. In 1776, the flag used was the Grand Union Flag, which looks much like an American Flag, with its 13 stripes, but instead of stars on a blue canton, the canton is simply the Union Jack, a replica of Britain's flag [source: Homer].

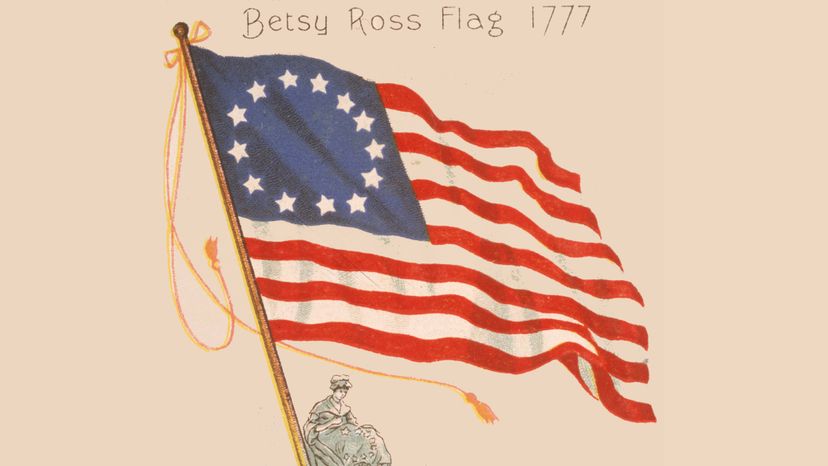

At some unrecorded point, the founders decided that having the flag of the enemy they were at war with as part of their own flag was a little odd, so the decision to replace the Union Jack in the canton was made. How the 13 stars in a circle on blue was settled on is lost to history, but there were quite a few variants, including a square of stars and stars arcing over the numerals "76." [source: Teachout].

The Continental Congress signed the Flag Resolution on June 14, 1777, but even then the details of the star pattern were in flux, and no one is quite certain where the idea to use stars at all came from. Theories include the influence of Masonic imagery on the Founding Fathers, or that they were adopted from George Washington's family crest, which does have some similarities to the stars and stripes flag.

The 13 stars in a circle design was gradually accepted as the standard, but even in 1779 there was ongoing debate about the flag's final form. Francis Hopkinson, a signer of Declaration of Independence, claimed to have designed the flag and requested payment for his services from Congress, which was denied, as even at the time they recognized that the specific design was the product of many ideas from many people [source: Williams].

There were many flag-makers in Philadelphia at the time of the Betsy Ross legend. It is certain that she made flags, and possible she made the first one. It's even possible she knew or met George Washington, either through her first husband's family connections or through church events (Washington was also an Anglican, or at least went to an Anglican church). However, it's unlikely he directly visited her to have the first flag made. And while Betsy Ross may have sewn the first flag (a worthy accomplishment itself), even if you believe every word of the legend, it's clear that she didn't design the flag beyond, possibly, changing the stars. That is, as well as we can ever know, the truth of the Betsy Ross legend.

But why did the legend become so firmly entrenched in American consciousness in the first place?