Key Takeaways

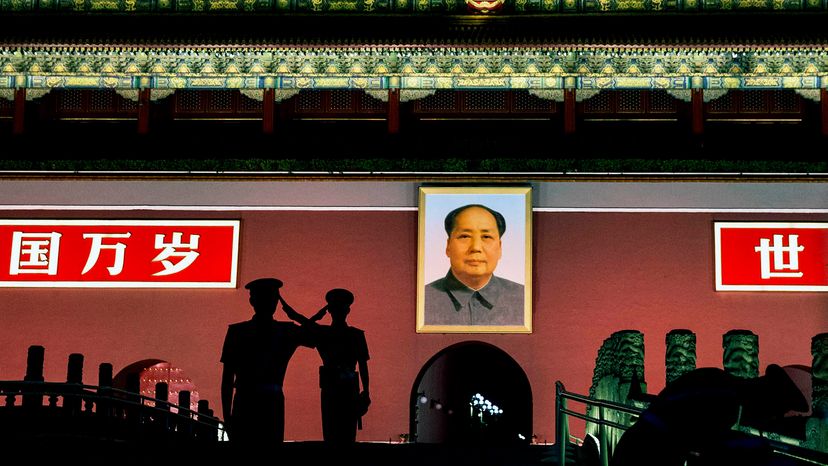

- Mao Zedong used controversial methods to transform China into a superpower.

- His rule was marked by disastrous policies like the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, resulting in millions of deaths.

- Despite his atrocities, Mao is still revered by many in China, and his legacy remains complex and divisive.

Mao Zedong was an unflinching dictator responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of his people — and yet millions in China still flock to Beijing to visit his grave, and billions celebrate his birthday every year.

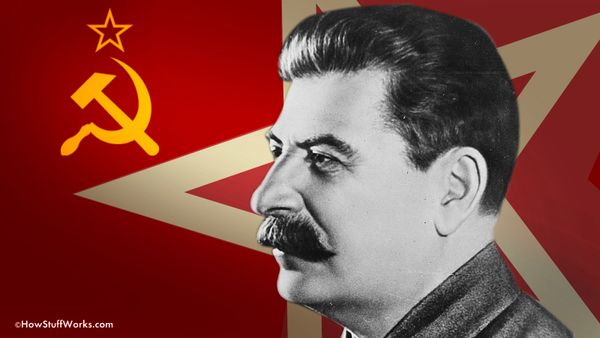

Mao was a visionary, a poet, a scholar and to some a demi-god who by virtue of his will and wisdom remade China from a poor country into one of the world's superpowers. Yet he is constantly grouped with 20th-century despots — madmen, murderers — like Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler.

Advertisement

Mao inspired the oppressed to take control of their oppressors. Yet he fought for most of his life to maintain his power, and the power of China's Communist Party, at any cost.

"Those who endured Mao's worst abuses execrate his memory," historian Jonathan Spence wrote in "Mao Zedong: A Life," a 2006 biography of the man who founded the People's Republic of China in 1949 and ruled the country until his death in 1976. "Those who benefited from his policies and his dreams still revere him, or at least remember the forces that he generated with a kind of astonished awe."

That was Mao. Complicated then. Complicated still. Even inside China. Maybe especially so there.

"The history in many people's minds is wiped out, not talked about, not mentioned. And the young people who don't know anything of that, they consider Mao as a national hero. The nationalistic appeal is so strong," says Xing (Lucy) Lu, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus at DePaul University in Chicago. She also wrote "The Rhetoric of Mao Zedong: Transforming China and Its People" in 2017. "They consider that a monument to Mao, because Mao stood up against the United States, the Soviet Union ... any superpower, he was not afraid of."

Advertisement