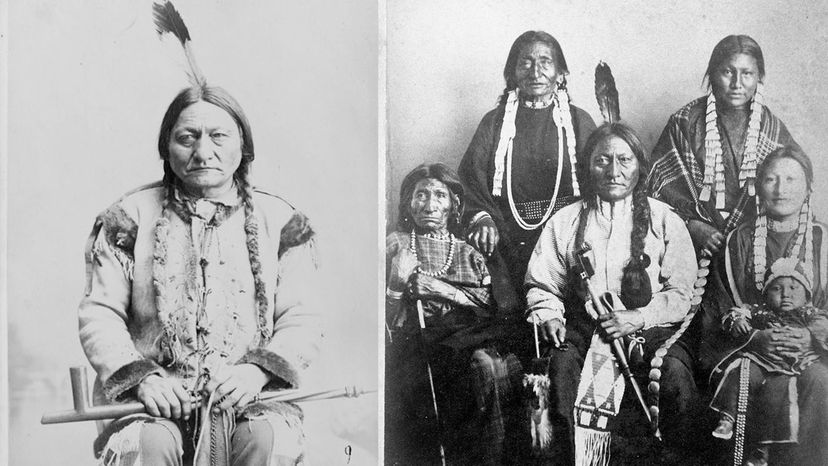

Despite being most known for the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn against the army of Gen. George Armstrong Custer, Sitting Bull was not at the fight in which Custer died, according to Anderson. He was associated with the battle and many would say he played a role in its results.

A rush for gold had led prospectors to move into the Dakota Territory's Black Hills despite the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, which held that the sacred land was off limits to white settlement. The U.S. government attempted to purchase the Black Hills, an offer rejected by the Lakota. In response, the government invalidated the treaty and decreed all Lakota must leave the area for reservations by Jan. 31, 1876. The Lakota refused to leave.

"In the end, you have several things colliding at once," says Anderson. Army officers were conspiring to start wars with the Sioux, of which the Lakota are a confederated tribe. There was a push to get the gold rush moving, which would necessitate U.S. government protection of miners. Furthermore, the Northern Pacific Railway was planned to be constructed through the Dakota territory.

"It's a complicated story, but Sitting Bull is at the heart of it," says Anderson. While three columns of federal troops converged on the area, Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes joined Sitting Bull's resistance.

It was the Oglala Lakota war chief Crazy Horse who led an initial battle against the army column under Gen. George Crook. At the Battle of the Rosebud, Crazy Horse forced the U.S. troops to retreat. The Lakota moved camp to the Little Big Horn River, where they were joined by 3,000 additional Indians.

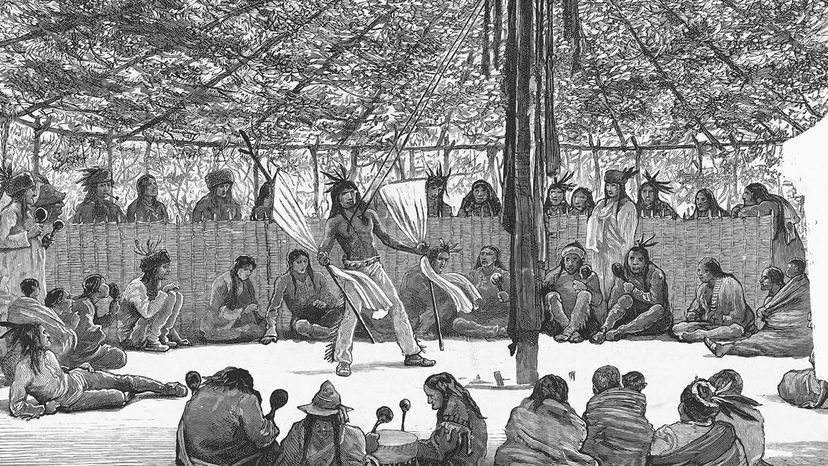

Sitting Bull led the Sun Dance ritual and offered prayers to the Great Sprit Wakan Tanka and slashed his arms between 50 and 100 times in sacrifice. He is said to have danced for 36 hours. It was during this ceremony that Sitting Bull had a vision of U.S. soldiers "falling into the Lakota camp like grasshoppers falling from the sky," which he interpreted as a portent of U.S. Army defeat.

The Seventh Cavalry under Custer attacked the Indians at Little Big Horn with just a few hundred men June 25, 1876. Crazy Horse led the Indians to victory, killing Custer and all of the U.S. soldiers on-site. Contrary to popular belief, Sitting Bull was not there. He was in recovery from the taxing Sun Dance, according to Anderson.

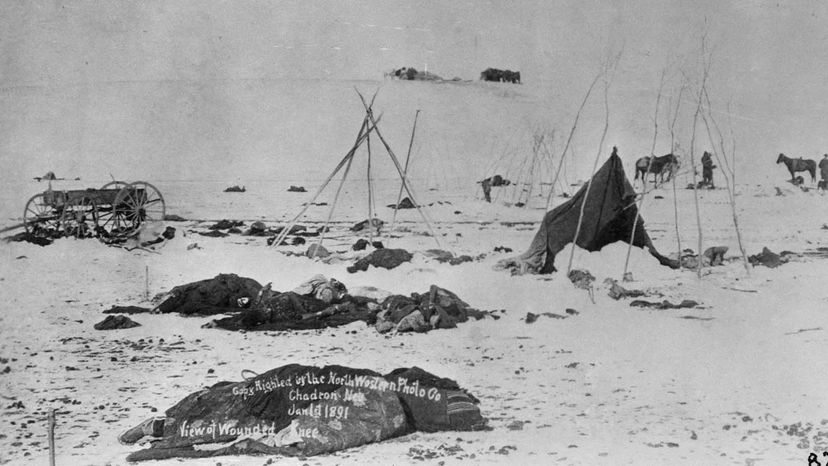

After the Battle of the Little Big Horn, the Lakota dispersed even as the U.S. Army hunted them down in retaliation for Custer's defeat. As some chiefs were forced to surrender, Sitting Bull took his people to Canada in 1877. However, the buffalo population had all but disappeared, and the Hunkpapa were starving. By 1881, Sitting Bull had no other choice but to surrender, too. For two years, he was held prisoner at Fort Randall before being allowed to return to his people, who were at Standing Rock Reservation in what is now North Dakota.