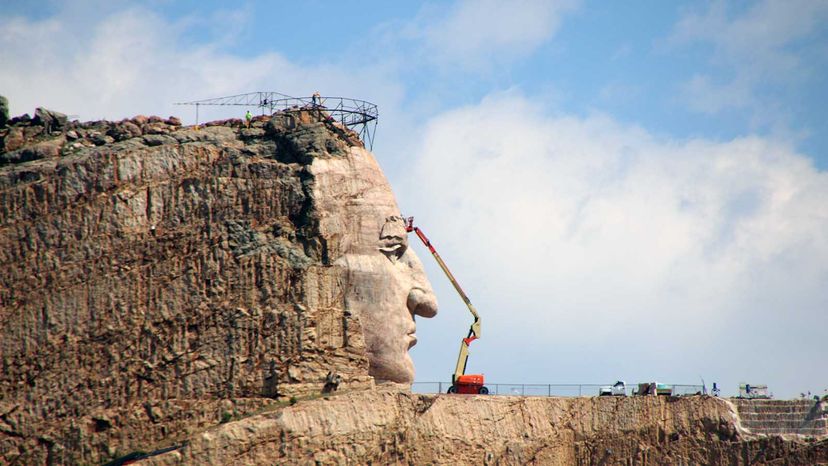

Begun in 1948, the Crazy Horse Memorial was slow to take shape in the first few decades of its existence. But it's clearly, if agonizingly, getting there. The front half of Crazy Horse's massive stone head — easily visible with a zoom-in on Google Earth or Google Maps — was completed in 1998, his eyes staring sternly to the southeast across the hills. A yet-to-be-finished outstretched arm points his way.

When the sculpture is finished — it's still probably decades away, at least — it will depict the chief, from the torso up, on the back of a horse. The horse's head, with flowing mane, will forever rest under Crazy Horse's arm.

"It really has been getting there. And people are starting to see that now. It's grown and changed so much in the last four or five years, it's incredible to see," Jadwiga says. "In the next six to 11 years, [we'll be finishing] the hand, the Indian's arm ... going back and finishing up the hairline at Crazy Horse's scalp, and always working on the horse's head, working down toward the horse's head and mane. You start at the top and work down."

The Crazy Horse Memorial (in non-pandemic years) is visited by more than 1 million people annually. The site now includes a welcome center, theaters, a Native American museum, a restaurant, an educational and cultural center, a "university" that sponsors educational programs that allow Native Americans to earn college credit and the inevitable gift shop.

Though there has been some controversy about the memorial throughout its history. Some Native Americans object to its place in the sacred Black Hills, some wonder whether it's all just a big money-making scheme, some bristle at the massive tribute to such a humble and mysterious man and some say that non-Indians should not be running the place. Though it's important to note that the project, on private land, never has accepted any federal or state money for its work. It's supported entirely by donations and visitors' fees.

For those who have long been working on the project — a crew of 15 spends five days a week blasting and chiseling the mountain into what Standing Bear and Korczak imagined all those years ago — the doubters, the impatient, the critics have proven to be not nearly as difficult to shape as the rock itself.

"There's a lot of people that never thought it would be done," Jadwiga says. "And it's not always been easy. You have your moments. My dad had a line; 'Everybody has a mountain ...' Each one of us in life has something that we're struggling with, that we have to get over."