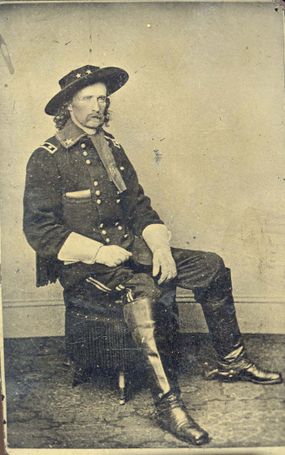

In 1896, exactly 20 years after General George Armstrong Custer was killed alongside 261 of his cavalrymen at the Battle of Little Bighorn, the beer company Anheuser Busch brewed up a wildly popular advertising campaign. The company reproduced 150,000 copies of a lithograph called "Custer's Last Fight!" and plastered it in saloons and taverns across America.

The lithograph, based on an 1888 painting by Cassilly Adams, depicts a chaotic battle scene on the Montana plains with a dozen blue-uniformed cavalrymen laying dead or wounded on the ground as war-painted Indians finish them off with clubs and spears before ceremonially scalping the white men's corpses. In the center of the violent scrum is a long-haired Custer dressed in fringed buckskin, raising his saber skyward to dispatch one last "savage" before succumbing to the overwhelming force of his attackers.

Advertisement

"More people 'learned' about what they think happened at Custer's last stand from this Anheuser Busch lithograph, and probably after a few Budweisers," says Tim Lehman, a professor of history and political science at Rocky Mountain College in Billings, Montana, and author of "Bloodshed at Little Bighorn: Sitting Bull, Custer, and the Destinies of Nations."

In American mythology, the popular notion of Custer's "last stand" echoes the story told in that 19th-century painting. Custer's down-to-the-last defeat ranks with the Alamo as a tale of white heroism in the face of "barbaric" aggression, of patriotic martyrs dying "with their boots on" to protect Western settlers.

But the real story of Custer's last stand isn't nearly so innocent, or cut and dry. On June 25, 1876, the Civil War cavalry hero known as the "Boy General" led a U.S. Army attack on an Indian village in the Black Hills in violation of a treaty promising those lands to the Lakota Sioux. Custer and his 7th Cavalry were clearly the aggressors, and if the Battle of Little Bighorn was anyone's "last stand," it was the Plain Indians'.

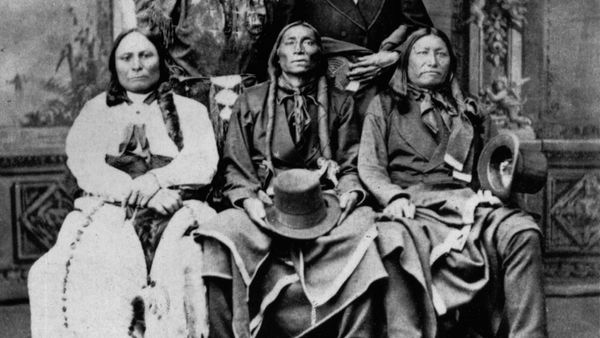

"It was crystal clear to Sitting Bull and the Lakota that they would be attacked that summer, and they saw the confrontation as one last great fight for their free way of living, before they had to submit to agencies and reservations and federal domination," says Lehman.

Advertisement