On Feb. 18, 1943, during the height of World War II, two German college students at the University of Munich entered one of the main campus buildings, walked to the top of a staircase and tossed a stack of leaflets over the railing and down into the crowded atrium. The leaflet, the sixth in a series of underground publications from a group calling itself the White Rose, exhorted fellow students to rise up against Adolf Hitler and the Nazi war machine.

"The Day of Reckoning has come," read the White Rose pamphlet, "the reckoning of our German youth with the most despicable tyranny ever endured by our nation ... Students! The German people are looking to us!"

Advertisement

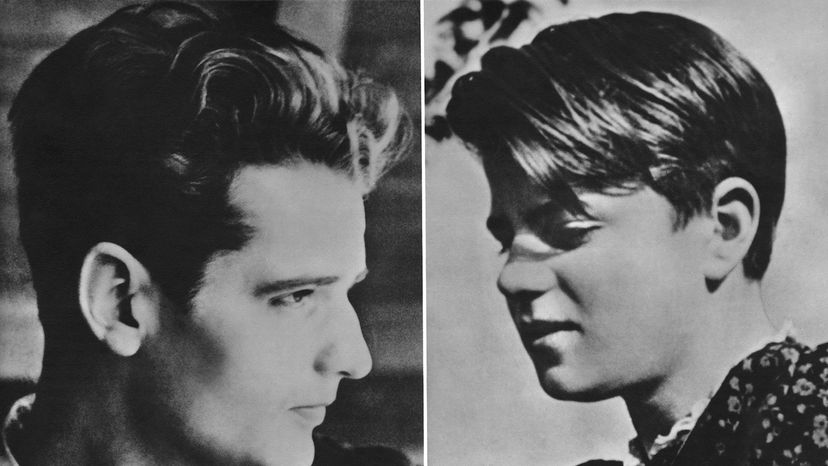

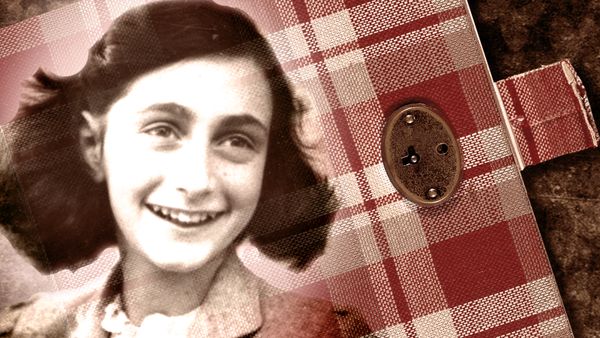

The two students who dumped the pamphlets at the University of Munich were grabbed by the janitor and handed over to the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police. They were siblings, Hans and Sophie Scholl. And within days, Hans and Sophie, and their friend Christoph Probst, were convicted of treason and executed. Many of their co-conspirators in the White Rose resistance movement were executed in the months that followed.

Today, the name Sophie Scholl is synonymous in Germany with courage, conviction and the inspirational power of youth. At just 21 years old, Sophie fought a murderous regime — not with guns and grenades, but with ideas and ideals.

Advertisement