Nowadays, presidential inaugurations in the U.S. take place on Jan. 20 and include parades, speeches and several sedate balls. Nothing like Andrew Jackson's inauguration, when complete mayhem allegedly broke out in 1829.

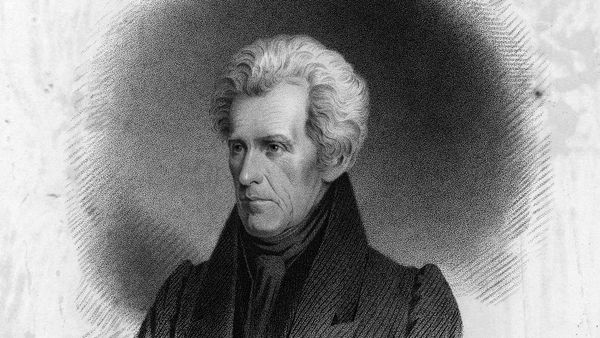

American presidential inaugurations used to be held in March, a full four months after the election. On March 4, 1829, a crowd estimated in the tens of thousands descended on Washington, D.C., to witness Andrew Jackson take the oath of office on the portico of the Capitol. The white-haired war hero known as "Old Hickory" gave a speech (which nobody could hear), kissed the Bible and bowed to the adoring throng.

Advertisement

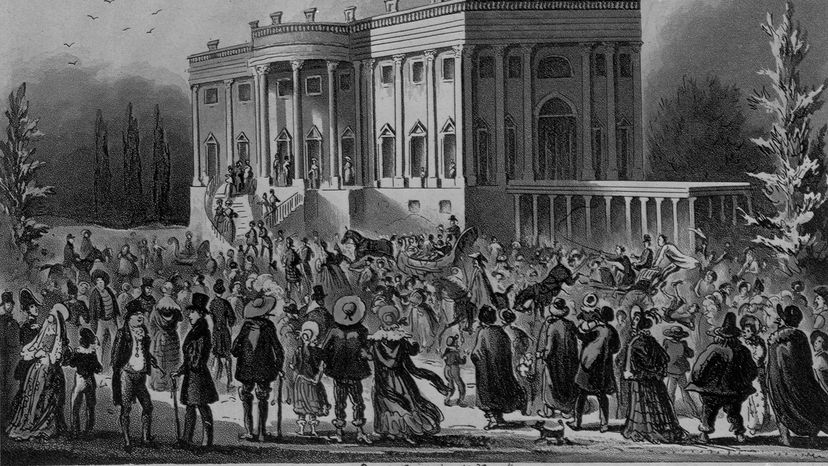

Jackson was America's first populist president, a straight-talking "outsider" candidate who vowed to represent the people, not the Washington elite. (He was the first president to win by appealing to the masses.) When the inauguration ceremony was over, the crowd broke through the barriers and rushed up the Capitol steps to shake hands with "the peoples' president."

"The living mass was impenetrable," wrote Margaret Bayard Smith, a Washington socialite and author. "Country men, farmers, gentlemen, mounted and dismounted, boys, women and children, black and white. Carriages, wagons and carts all pursuing him to the President's house."

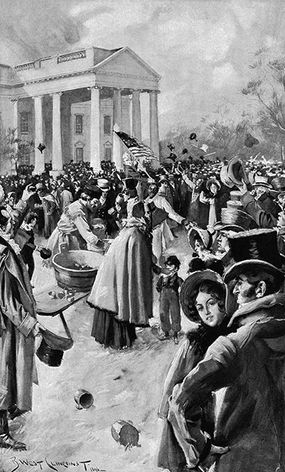

But what happened next is the only thing that most Americans know about Jackson's inauguration. Following a tradition established by George Washington, Jackson held a "levee" back at the White House, an "open house" of sorts where regular citizens could mingle with the new First Family. And that's when things allegedly got out of control. Way out of control.

"This is the iconic event that everybody knows about today, when thousands of people — 'dirty' people with mud on their boots who, according to the genteel, should not have been there — stormed the White House and created total chaos," says Daniel Feller, an emeritus history professor at the University of Tennessee and editor of The Papers of Andrew Jackson. "People standing on chairs to get a better view, grabbing for food and drinks to the point that tables are overturned and being shattered. This is the story that you've probably heard."

Advertisement