The Inca believed they were on to something with child sacrifice. The ritual killing of perfectly beautiful children high in the Andes Mountains wasn't something they took lightly. When a child was offered by his or her parents as a sacrifice, the Inca held feasts in the child's honor. They wished the child well during the procession through villages to the mountain peaks where the ceremony would be held.

Workers built a ceremonial chamber, and the child received corn alcohol to stave off fear. Scientists debate how the children died, but explorer and anthropologist Johan Reinhard believes they died from exposure to the elements. Before that happened, though, a cushioned blow to the head knocked the child out, to help prevent suffering. The child's parents would often return to the site of the sacrifice to bring further offerings [source:Clark].

Advertisement

"This was the ultimate sacrifice the Inca could make to please the mountain gods: to offer up their own children in the highest places humans could possibly reach," writes NOVA producer Leisl Clark [source: Clark].

The concept of human sacrifice is a difficult one for many modern people to accept. A tenet of anthropology, however, is cultural relativism: To understand a culture, one can judge that culture only by its own standards, not by another culture's standards. This holds true for all cultures past and present, and through this lens, the motives of a people come into focus.

The Inca didn't sacrifice children for sport or because they didn't value their young. The ritual was a solemn, dignified process by which the Inca hoped to appease their gods. On the contrary, children were sacrificed because they were valued by the Inca: To sacrifice such a valuable part of their society was to show their devotion to their religion.

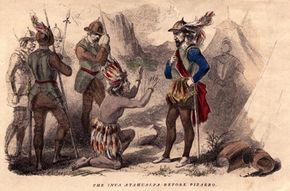

To them, it must have seemed as though their sacrifices pleased their gods. The very successful Incan empire stretched 2,500 miles from modern day Ecuador to Chile [source: University of Colorado]. It reached a population of more than 1 million people just a couple hundred years after its founding. Through technology, might and communal society, the Inca tamed the Andes. And yet, when the Spanish came, it took fewer than 200 men to bring down this civilization in the sky.

How did this happen? Find out on the next page.