Most people can recount a rough outline of Joan of Arc's story: A young French girl hears voices, leads troops into battle and is burned at the stake as a heretic. It's a legendary tale of bravery passed along since the Middle Ages. Renderings of her youthful face have rallied together nations, races, genders and movements. References to the Maid of Orléans appear in the writings of Shakespeare, Henry Longfellow, Mark Twain and George Bernard Shaw, to name a few. During World War I, U.S. Treasury Department propaganda posters urged women to buy war bonds, proclaiming "Joan of Arc Saved France." In short, Joan of Arc's legend has come to represent the ultimate example of courage, patriotism and religious devotion.

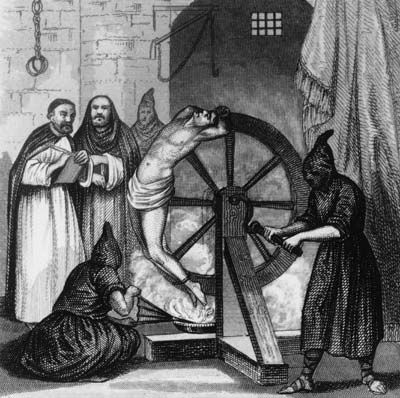

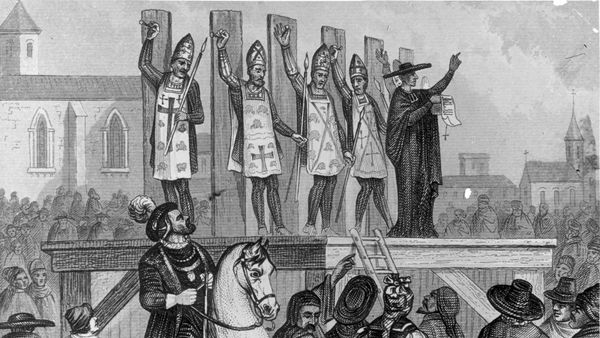

But while we often get the primary plot points of Joan's brief life correct, the ending has been botched repeatedly. True, she was burned at the stake at the age of 19, but it wasn't for heresy or witchcraft, as the story often goes. In the end, the only crime that the Inquisition tribunal could formally charge the chaste maiden with was that of wearing men's clothes. The winding logic that led the judicial panel to condemn a person to death for her sartorial choices illustrates not only the genuine military threat that Joan of Arc posed to the English, but also the extreme lengths the Catholic Church was willing go to maintain its tight control over Europe during the Inquisition.

Advertisement

Two major religious and political conflicts had been brewing for a while in France and the rest of Europe when Joan of Arc led the epic siege of Orléans in 1429. In 1231, Pope Gregory IX initiated the Inquisition to purge any heretics out of the Catholic Church. Two centuries later, that tribunal system of ecclesiastical courts was alive and well among the clerics in England and France.

England and France were also embroiled in the latter part of the Hundred Years War (which actually lasted 116 years). The conflict began in May 1337, when King Charles IV of France died without an heir to the throne. Intermarriage between French and English nobility incited a debate between King Edward III of England and Philip the Fair of France over who would claim the throne. In 1420, it appeared that the war might come to an end with the Treaty of Troyes, which guaranteed Henry V of England the French throne once Charles VI died. But Henry died in 1422, and Charles followed in suit two months later, rendering the treaty void -- and reigniting the military conflict.

Advertisement