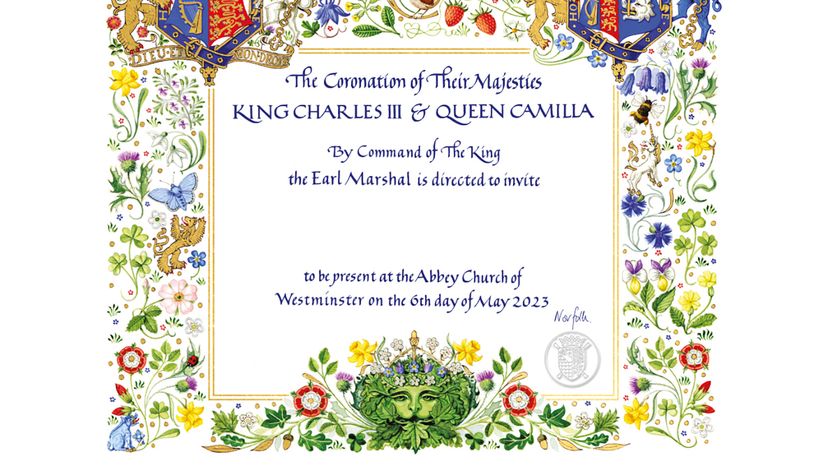

The official invitation for the coronation of King Charles III is creating a bit of a stir. On the bottom border of the ornate invitation is a depiction of the "foliate head." It's a Green Man's smiling face, his beard and hair made of ivy, oak and hawthorn leaves, mixed with a jumble of multicolored flowers that bleed into the border of the invitation. What's not to like?

Advertisement

Who Is the "Green Man"?

The Green Man is one of the most popular decorative tropes in England, and sculptures of his leafy mug can be found looming over the ceilings of medieval churches or peering up from garden paving stones all over the U.K. and Europe. Various renderings depict him in different ways.

On the coronation invitation he appears friendly, but depending on who depicted him, he can look terrified, leering, stoic, angry or downright demonic. His face, leaves often sprouting from his open mouth, nostrils or eye sockets, can be obscured by greenery as if he's peeping out, or the foliage can even overtake and meld with him, replacing some of his human features.

Although the Green Man is one of the most common artistic motifs in 13th and 14th century churches around the U.K. and Europe, the story we tell about him today is overtly pagan — a symbol of spring and rebirth, or of nature's ultimate supremacy over humanity. His connection to the ancient history of the British Isles is up for debate, but his face on the invitation to an ostensibly Christian coronation ceremony is causing a bit of uproar.

Advertisement

Where Did the Name "Green Man" Originate?

But the Green Man is a tricky guy because although his face is everywhere, his reputation as a powerful pre-Christian nature deity was cooked up less than a century ago by a British aristocrat and folklore buff named Julia Somerset, or Lady Raglan. She named the foliate head seen in English churches the "Green Man," and invented a fairytale about his origins in a 13-page article in the March 1939 issue of the journal "Folklore."

In her article, Somerset not only assigned a name to the foliate head — she likely got "Green Man" from the many English pubs with that name — but also identified him as an ancient god of fertility and strength. She went on to speculate that ancient pagans might have engaged in ritual human sacrifice each May Day, identifying a male member of the community to represent the god, hanging the man from a tree or decapitating him and placing his severed head in a tree.

Of course, there is no scholarly evidence to back up Somerset's claims, but the gruesome story of pagan brutality and hedonism became wildly popular in the U.K. Since then, the Green Man has been plastered all over English pubs, inns, gardens and music festivals — there is a Green Man music festival in the U.K., and the Burning Man Festival in the U.S. made the Green Man its theme in 2007.

If the foliate head did in fact represent a powerful pagan god for whom the ancients ritualistically decapitated people, it really would send a bit of a disturbing coronation message; however, that's almost certainly not the case. Depictions of leafy-headed men are by no means unique to the U.K. — versions of the foliate head have been found in sixth-century Istanbul, alongside Greek depictions of Dionysis.

So, why is the Green Man found in so many Christian churches throughout Europe? Early Christians likely saw the Green Man as a symbol of the cyclical nature of Christianity, as a nature-centric representation of the Holy Spirit which breathes life into the world, and the leaves, vines and flowers flowing from him a symbol of rebirth.

No matter where or when the Green Man came from, he has become a neopagan icon, a symbol of English folklore, and eventually was adopted by the New Age movement in the 1960s. He might have made his way into hundreds of churches all over Europe, but his roots are vague, however inspiring of countercultural nature worship. Modern pagans sometimes worship him, however, which does make his visage an unusual choice for a coronation invitation, because it seems to be inviting controversy.

Perhaps by reading "Robin Hood" or "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight," we might learn more about what the Green Man has to teach us because, although he may be watching, the mysterious Green Man isn't talking.

Advertisement