As with so many colorful characters who lived during the heyday of the American Wild West, there are a lot of uncertainties about the life of Tom Horn. What no one disputes, however, is that Horn killed a lot of people. The notoriety he earned through bloodshed made him an icon of the frontier, so renowned (and feared) that some people believe that Horn's spirit lingers to this day, haunting the Rocky Mountains and desert plains where he once stalked his human prey.

Born in 1860 in Missouri, Horn was the fifth of 12 children and suffered an abusive upbringing that he fled when he was just 14. Two years later he became a scout for the Army out West, where he learned Spanish, and some Apache, and became useful as an interpreter during the Apache Wars. He played a small role in helping translate surrender terms between famed Apache leader Geronimo and U.S. forces.

Advertisement

After the war, Horn restlessly wandered the West, sometimes working as a ranch hand, prospector, deputy sheriff, U.S. Marshal and rodeo competitor.

After a few drinks, Horn had an eye-rolling propensity for bragging about his exploits, telling anyone within earshot about his adventures and his courage in the face of gunfire.

He wasn't all talk. His second-to-none tracking skills caught the attention of the famed Pinkerton National Detective Agency, which hired him to locate and apprehend wanted men throughout the West. But his propensity for extreme violence made him a suspect in the killings of several fugitives. Horn's behavior was a public relations risk for Pinkerton, so the company forced him to resign his position.

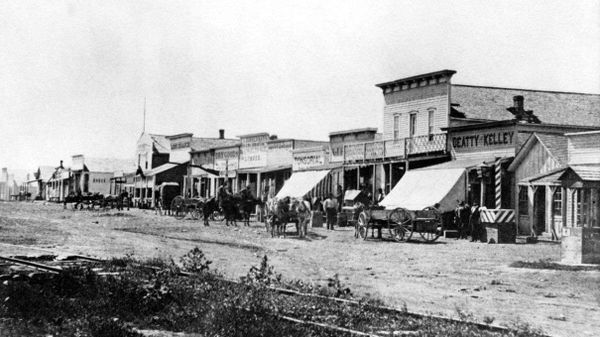

By then, Horn's skillset dovetailed neatly with a series of 1890s frontier conflicts. As more and more homesteaders established ranches, they clashed with cattle barons who'd previously had free run of the land. With more people competing for grazing land and water, the bigger, more established players took extreme measures to root out the little guys.

Some went so far as paying for hired guns, like Tom Horn, who intimidated and threatened homesteaders into abandoning their land.

One man, named Kels Nickell, was a Wyoming sheep herder who had a run-in with a baron named John C. Coble. "Kels Nickell had a lot of enemies. The irascible rascal had managed to offend most of his neighbors," says Marshall Trimble, an author and official state historian in Arizona in an email interview. "In a scuffle with John Coble, Nickell pulled a knife and inflicted a near fatal wound on him. Coble carried a grudge. A Cheyenne resident had this to say, 'Coble hates Nickell like the devil hates holy water.'"

"When the rich cattlemen wanted to bully [Kels], they were messing with the wrong guy," says Joe Nickell, an author and paranormal investigator with the Skeptical Inquirer. (He's also a very distant relation of Kels Nickell.) "He wasn't the guy you [could] run off his property, so they [the cattle barons] knew they had to kill him."

And that's where Tom Horn came in.

Advertisement