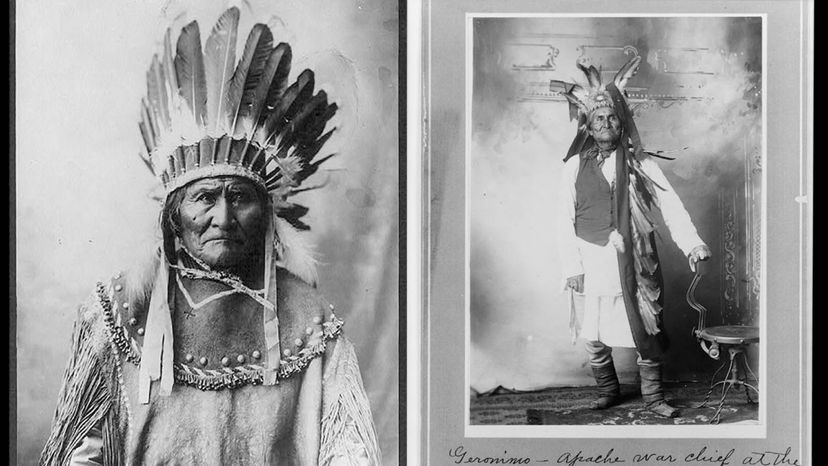

Geronimo's life story often veers from his legend: He was depicted in U.S. and Mexican culture as a frighteningly fierce warrior and as a representative of bravery for the World War II paratroopers who yelled his name as they jumped from planes. He was called "the most famous North American Indian of all time," by one of his biographers.

But in reality, Geronimo was less of a mythic figure to his people. In fact, he was relatively unknown outside the Chiricahua Apache until he reached middle age, according to The Washington Post.

Advertisement

"In our tribe, Geronimo was not a very important person," says Michael Darrow, Fort Sill Apache tribal historian. "He was not a chief." A century ago, Geronimo wouldn't have been a big deal to the tribe.

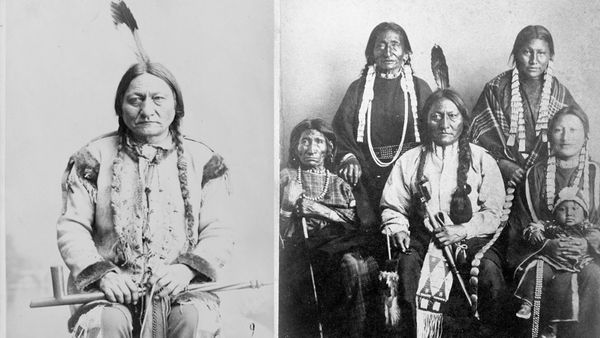

Yet to many Americans in the 19th century, Geronimo epitomized the trope of the fierce warrior Indian. He represented the rhetoric that could be used to justify "protecting" settlers by moving Indians onto reservations. And that rhetoric was applied to the Apache more generally.

"One of the things that is very common in writing about Apache is to use the term warriors," Darrow says. However, the Apache language doesn't have a term that translates to warrior. "History books, and as a result, the popular portrayal of Apache in books and movies, are that Apache are fierce and warlike."

Geronimo's own telling of his childhood offers a different story.

Advertisement