Abraham Lincoln knew exactly why the Declaration of Independence was such a profoundly important political document.

"I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence," said Lincoln in an improvised speech on the eve of his first inauguration. "I have often inquired of myself, what great principle or idea it was that kept this Confederacy so long together. It was not the mere matter of the separation of the Colonies from the motherland; but that sentiment in the Declaration of Independence which gave liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but, I hope, to the world, for all future time."

Advertisement

Lincoln was one of many American leaders and civil rights activists who challenged the nation to live up to its founding principles as enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, "that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

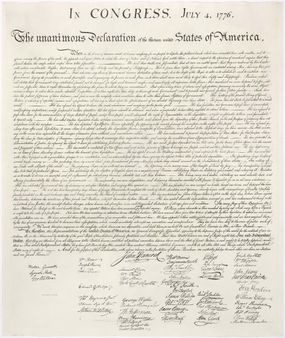

But there's much more to the Declaration of Independence than that one unforgettable sentence. In 1,337 words, Thomas Jefferson and the rest of the Continental Congress made the case to their fellow Americans and the world that they had suffered abuse and mistreatment under King George III and that the British parliament intended to take away their freedoms. Colonists had no choice but to cut ties with Great Britain and declare themselves "free and independent states."

Advertisement