A famous pharaoh, a mysterious name written on all of his burial treasure, and a possible secret tomb hiding in plain sight for almost a century — all the makings of a great ancient Egyptian mystery. And it gets better: this tomb might contain the remains of one of the only women to rule over ancient Egypt.

Admit it — you're interested.

Advertisement

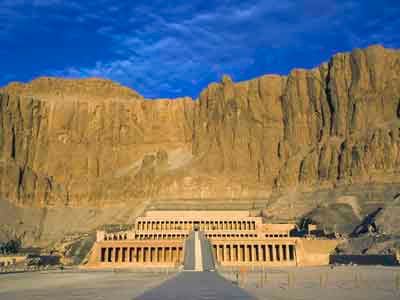

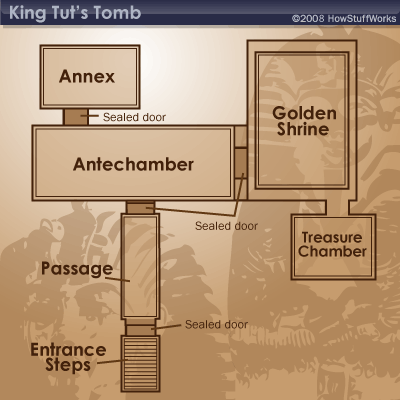

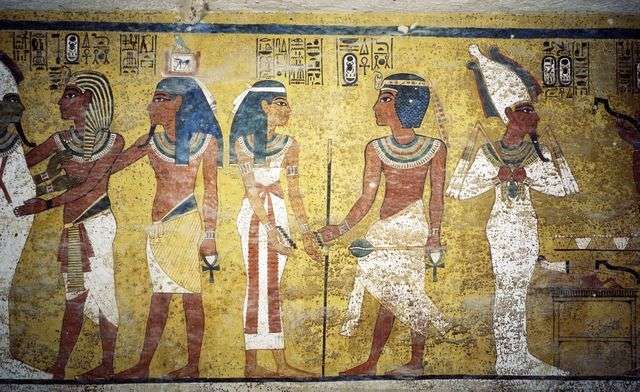

Last year, British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves of the University of Arizona published a paper online titled "The Burial of Nefertiti?" Using high-resolution scans of the walls of King Tutankhamen's tomb, Reeves discovered irregularities in the walls that suggest doorways that were blocked up and plastered over before the burial of the famous pharaoh. King Tut's tomb is something of an anomaly, due to the fact that the layout and art seem to have been designed for a queen rather than a king. In his paper, Reeves suggests this might be because it was originally designed for Tut's stepmother, Nefertiti, whose tomb has never been found.

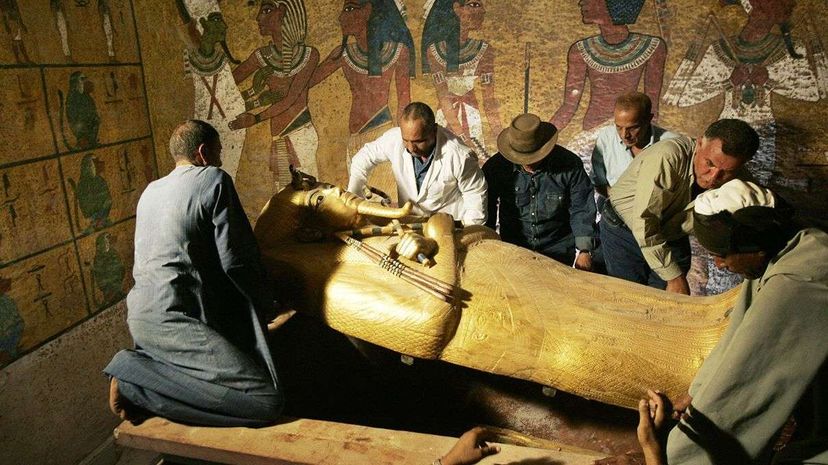

King Tutankhamen was actually a lesser pharaoh of ancient Egypt, but these days he's a pretty big deal. Rising to power at just 9 years old, and dead by 19, he probably wasn't a very influential king, but due to his relative political insignificance and sudden death, his mummy was interred in a small tomb, which was buried in rubble a few hundred years later by workers carving out a site in the Valley of the Kings for the tomb of Ramses IV. As a result, Tut's tomb was overlooked by grave robbers for over 3,000 years until its discovery by archaeologist Howard Carter and his patron Lord Carnarvon in 1922, making it the first intact royal Egyptian tomb discovered in modern times. It contained thousands of pieces of art, furniture, and jewelry, many of which bore the name of Tutankhamen. But what's always puzzled Egyptologists is why King Tut's name was painted over that of another pharaoh: Smenekhkare.

"It's possible there's a whole story within a story that was right under our noses," says Egyptologist Stephen Harvey, director of the Ahmose and Tetisheri Project. "It took many years to dig out and prepare one of these tombs, along with all the golden objects, the coffins, the thrones and chariots and everything else. When a pharaoh died unexpectedly, they'd have a problem. What seems to have been done is a lot of material was actually reused — not just once, but some of them over and over again."

Nicholas Reeves has been looking closely at Tutankhamen's burial for decades, and when the Getty Museum in Los Angeles made full-scale scans of the wall decoration in King Tut's tomb, Reeves was able to virtually zoom in super-close on the murals, and even to remove the paint to examine the wall itself. When he removed the paint, Reeves found what looked like blocked-up doorways.

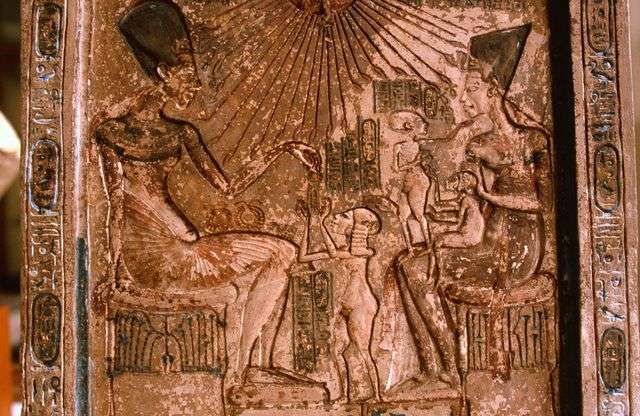

"Let's just say if all Reeves found was a blocked up doorway in Tutankhamen's tomb, that's still pretty exciting," says Harvey. "But he ended up published an article arguing that the original tomb equipment was made for Queen Nefertiti, who was, in his opinion, briefly on the throne of Egypt as a pharaoh, which was a male gender identity."

Though there's significant debate among Egyptologists about the issue, it's Reeve's opinion that Smenekhkare was the masculine name adopted by Nefertiti when she rose to the throne, and that her reign directly preceded Tutankhamen's. When Tutankhamen died before his any of his funerary equipment was ready, they just repurposed Nefertiti's equipment and walled off her burial chamber, burying the boy king in the other side.

In 2015, thermographic and radar scans done on the walls of the tomb suggested there might be a hidden chambers behind the wall, and that the chambers might contain metal and organic material. In March, however, a team of National Geographic radar specialists were unable even to replicate results that said there was a chamber behind the wall.

"The Valley of the Kings is made of limestone, and the ancient Egyptians dug down through different strata until they got to the purest, whitest stone," says Harvey. "Sometimes they had to dig past layers of flint, which is a really hard stone. From what I understand, this flint can make radar or sonar results very hard to read. Maybe we should just hold out for when we have better technology."

In just a few months, what was at first a theory set forth by a respected Egyptologist has become a hot political issue. Since Reeves' article was published last year, the Egyptian minister of antiquities has changed, from Mamdouh Eldamaty, who was very pro-Reeves, to Khaled El-Enany, who recently declared at the Second Annual Tutankhamen Grand Egyptian Museum Conference in Cairo that "no physical exploration will be allowed unless there is 100 percent certainty that there is a cavity behind the wall."

The conference included a yelling match between Eldamaty and the former antiquities minister under President Hosni Mubarak, Zahi Hawass (who is something of a celebrity in Egypt, with his own clothing line and reality show).

"When this first came out and I read [Reeves'] article, I had to fan myself," says Harvey. "It would be one of the most extraordinary stories in history: we have what we think is the greatest treasure ever found, and there's a whole other one behind it. It's like something out of a movie. But if you ask me today if I think we'll have any clarity on this in the coming year or two, I'd probably say no."

Advertisement