On July 3, 1941, a little more than a week after the Nazi German invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II, Joseph Stalin spoke for the first time to the Soviet people about the progress of the war. He called the citizens of his nation "brothers and sisters," a term he had never used before.

It was an intimacy born of the terrible crisis they shared. Stalin admitted that the enemy had succeeded in breaking through, and he urged his compatriots to annihilate the intruders with every means possible.

Advertisement

Many Soviet memoirs attest to the power of his words, which reached out to millions of citizens clustered around primitive radios or streetside loudspeakers. The Soviet people were urged to rouse themselves for what was to become the largest military contest of all time.

The Axis assault on June 22, 1941, had caught Soviet forces almost entirely unprepared. Finnish armies in the north, Romanian armies in the south, and a 3-million strong Nazi German force between them drove forward at a relentless pace, encircling whole Soviet armies.

On June 28, 1941, Nazi German forces reached the Belorussian capital of Minsk. Riga was captured three days later, and by the first week of July Nazi German armies were approaching the Ukrainian capital of Kiev.

By late July, Nazi German bombers came within range of Moscow. By August 19, Leningrad — the Soviet Union's second largest city — was cut off by Nazi German and Finnish forces, though it could not be captured outright.

Soviet officers pushed their soldiers to make suicidal attacks on Nazi German positions, as Stalin insisted that death was better than surrender. Nonetheless, by September, Axis troops had rounded up more than 2 million Soviet prisoners and destroyed much of the Red Army's tank and aircraft strength.

By October 3, when Adolf Hitler flew back to Berlin to address the German people, he was confident that the Soviet dragon was killed "and would never rise again." Nazi German production plans for weapons were changed: Large numbers of aircraft and additional naval power were added for the coming confrontation with Britain and the United States. New models of tanks had, however, been ordered, as the Nazi Germans discovered that Soviet tanks were superior to their own.

Hitler's changing strategic vision was a reaction to the increasing collaboration between the two Anglo-Saxon powers. Though U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt was constrained by a public opinion that was not yet prepared for full-scale belligerency, the United States had begun to give the British Empire extensive assistance.

In December 1940, Roosevelt had introduced a program of aid for Britain. It was called Lend-Lease to give the impression that something eventually would be given back. In March 1941, the plan passed through Congress. So relieved was U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill that he described Lend-Lease as "tantamount to a declaration of war."

At the same time, the U.S. Navy entered the great naval conflict in the Atlantic, where Nazi German submarines threatened the vital trade lifeline from North America to Britain. This conflict cost the Allies 5.6 million tons of shipping from September 1939 to March 1941.

In April 1941, the U.S. Navy began to cover part of the western Atlantic Ocean, and in July 1941, it began anti-submarine air patrols from Newfoundland. Consequently, convoy shipping across the Atlantic became more successful.

The Anglo-American relationship was sealed in August 1941 when Churchill and FDR met aboard the American cruiser Augusta at Placentia Bay off the coast of Newfoundland. There, Churchill sketched out a document, which would become known as the Atlantic Charter, for the two statesmen to sign.

It was not an alliance, as Roosevelt neither wanted nor could make a formal commitment to American belligerency. Instead, it was a statement of common political intent made in the name of liberal democracy for the restoration of a world based on political freedoms, open trade, and the self-determination of peoples.

In private, the two men also agreed to give all possible help to the Soviet Union, to warn Japan against further encroachments in the Far East, and to involve American forces more fully in the Atlantic battle.

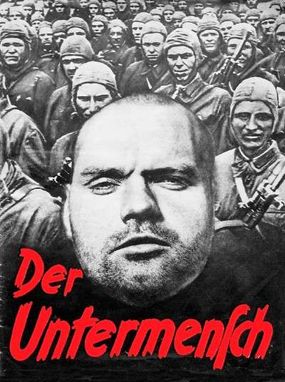

The summer of 1941 marked the beginning of the mass murder of Europe's Jews. Between the outbreak of war and June 1941, Jewish populations under Nazi German control in Eastern Europe had been herded into ghettos, their valuables seized and their livelihoods destroyed.

In occupied Western Europe, Jews were compelled to wear the distinctive yellow star, and their property was seized or handed over on unfavorable terms.

But only with the invasion of the Soviet Union were Jews systematically murdered. Pre-1941 instructions to Nazi German security units, the Einsatzgruppen — and to units of the regular police — made it clear that they should kill all Jews.

On the assumption that most partisan activity was Jewish-inspired, whole villages were destroyed and their inhabitants murdered by the Nazi German army as well as by the police and security units.

From June 1941, Nazi security forces in Russia did not spare Jewish women and children. At Babi Yar outside Kiev, more than 34,000 Jews were slaughtered. In Serbia and in western Poland, Jews were killed systematically.

Hitler at last approved deportation for German Jews as well, and the first trainloads arrived in the East in October 1941. At some point, a decision was made to augment the continuing murder by police and security men with mass murder at extermination camps in occupied Poland.

The precise moment of this decision is unclear, but the camps were under construction beginning in autumn 1941 and the first gassing began at Chelmno in January 1942. In December 1941, Hitler told an assembly of party leaders in a closed session that global war signaled a final war to the death against the Jewish enemy.

The mass killing that began in 1941 ended in 1945 with the estimated death of approximately 6 million European Jews. They were killed not only by Nazi German security forces, but by the Wehrmacht, locally recruited anti-Semitic militia, and the troops of Nazi Germany's allies.

Only some of this race war was evident to the West in 1941. The United States was much more concerned with the threat to security posed in East Asia and the west Pacific by the continued belligerence of Japan. This was a crisis brought on by the German victories in Europe.

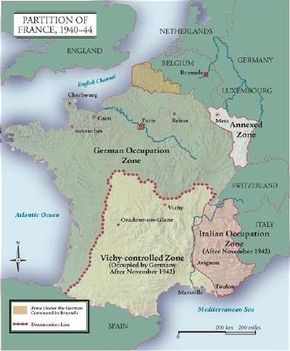

Japan had used the opportunity presented by the defeat of France and the Netherlands, and the Nazi German threat to Britain, to pressure western colonial possessions in Southeast Asia. Japan coveted this area because it contained large reserves of vital raw materials — oil, rubber, and tin in particular — which were essential for the Japanese war effort.

The American reaction to continued Japanese aggression in China had been to impose a partial trade embargo in September 1940, but that only heightened Japanese determination to seize further economic resources. Japanese leaders began to argue that war with the United States was almost inevitable.

The driving force behind Japan's strategy of southward expansion was its huge navy, which relied heavily on oil. To secure the northern perimeter of the Japanese empire, Japan signed a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union in April 1941.

In July, Japanese forces moved into southern Indochina. When the United States responded to this threat by tightening the embargo, the Japanese army and navy agreed that unless diplomatic pressure could undo the economic stranglehold that Tokyo had anticipated, they would attack the United States, the Dutch, and the British Empire.

The Japanese war was not inevitable. However, once Nazi Germany had invaded the Soviet Union and apparently removed the threat from Japan's northern frontier, the southward advance became an attractive option for the Japanese leadership.

During all of 1941, the Germans viewed the idea that Japan would occupy the United States in the Pacific as a strategic bonus. The Germans, in fact, urged Japan to do so, promising the Japanese that they would join in war against the United States.

In September 1941, the Japanese armed forces presented Emperor Hirohito with a plan for war if the United States did not end the embargo through diplomatic agreement. The emperor favored a solution short of war, and for two more months negotiations continued between Japanese and American officials to find a formula for peace.

American intelligence could read the Japanese diplomatic (but not naval) codes and knew that war was a very strong possibility. When General Tojo Hideki became Japan's prime minister in October, he set a deadline of November 30 for negotiations. This deadline was intercepted and decoded by the Americans.

Meanwhile, the Japanese navy developed detailed operational plans to secure a Pacific perimeter to protect seizure of Malaya, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies.

On November 26, U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull sent a set of proposals to the Japanese negotiators that included the withdrawal of all Japanese forces from China and Indochina. Subsequently, it was suggested that if the Japanese would withdraw from southern French Indochina, they could buy all the oil they needed, but Japan insisted on war.

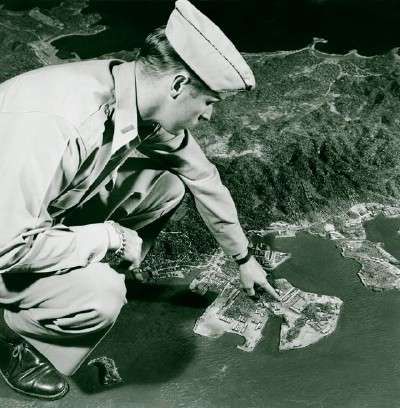

A task force of six fleet aircraft carriers and accompanying warships approached the Hawaiian Islands. Undetected on the early morning of December 7, 1942, Japanese planes attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet stationed in Pearl Harbor, destroying or damaging more than 300 planes and eight battleships and killing more than 2,000 men. President Roosevelt summoned Congress, which voted to declare war that same day.

The opening of a second major theater of war meant that even more of the world was engulfed in the conflict. Japan fought to achieve an Asian and Pacific new order, as Nazi Germany and Italy fought for domination in Europe and the Mediterranean.

On December 11, Hitler declared war on the United States. Having planned for war with the U.S. since the 1920s, but not yet having built the warships for that conflict, he now had a navy on his side.

War meant that German submarines could attack U.S. shipping without restriction. It also meant that Germany — now aided by a powerfully armed Japan — could begin the contest for a world in which, in Hitler's warped mind, only Nazi German or Jew would triumph.

Hitler's ongoing war with the Soviet Union, however, was no sure thing. In December, Red Army divisions began a major offensive around Moscow to force back Nazi German armies that had been prevented from capturing the capital.

Against German soldiers who were at the end of tired supply lines in cold weather — for which the Germans had not prepared — the Soviets made substantial progress. The German army had already been driven back at the southern end of the front in late November. Soon after the German defeat before Moscow, they also suffered a defeat at the northern part of the front.

This news thrilled Churchill, as did America's entry into the war. After Pearl Harbor, he telephoned Franklin Roosevelt, who told Churchill that Britain and America were "in the same boat now."

His words were hauntingly ironic. A few days later, the British battleship Prince of Wales — which had transported Churchill to negotiate the Atlantic Charter — was sunk by Japanese naval bombers in the South China Sea.

The next page highlights the major events of World War II during the early part of July 1941.

Advertisement