The first several months of World War II -- nicknamed the "Phony War" -- began and ended with the German invasion of neighboring states -- Poland first, in September 1939, and then Denmark and Norway in April 1940. Here, the similarity ended. Nazi Germany invaded Scandinavia in 1940 due to Germany's naval war against the British and their American suppliers, and to protect the winter route for iron from Sweden. And unlike the invasion of Poland, the attacks on Denmark and Norway launched a permanent state of fighting in Europe that lasted right down to German defeat in May 1945.

World War II Image Gallery

Advertisement

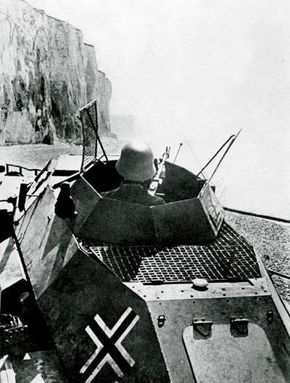

The brief northern campaign was one of the most successful of Hitler's gambles. On April 9, German forces entered Denmark and occupied the peninsula without serious resistance. A seaborne and airborne force, covered by a German air screen, then invaded Norway. Despite stubborn Norwegian resistance, and the landing of British and French troops in support in northern Norway, the Norwegian government agreed to an armistice on June 9. However, many German warships were sunk or damaged in this operation.

On May 10, Adolf Hitler had his forces in the West -- after months of patient preparation -- launch the attack on France through the Low Countries and the Ardennes Forest farther to the south, which the Allies had thought impassable by a modern army. A few hours after German troops crossed the Dutch border, an act of long-term significance took place in London when Winston Churchill succeeded Neville Chamberlain as British prime minister. At that moment, Churchill later wrote, "I felt as if I was walking with destiny."

The first weeks of Churchill's premiership proved disastrous for the Allies. German plans to push heavily armored divisions along forested terrain, supported by waves of aircraft, succeeded well beyond the expectations of many German generals. The French defensive line was pierced, and within days a gap burst open in the Allied front that could not be closed. The British Expeditionary Force was pushed back toward the sea around the port of Dunkirk, France, and faced annihilation -- until General Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt and Adolf Hitler ordered German forces to stop on May 24 to refit and prepare to break the new French defense line further south. By the time the attacks began again on May 26, the British had planned a hasty marine retreat. By June 4, 338,000 troops, one-third of them French, had been evacuated.

Though the "miracle of Dunkirk" has long been celebrated in Britain, it represented an ignominious defeat. The surviving French resistance slowly crumbled. On June 14, German forces entered Paris; on June 22, the French sued for an armistice, and German victory was complete. While a similar campaign during World War I had lasted four years and cost the lives of 1.5 million Germans, this campaign was over in six weeks. This time, Nazi Germany lost 30,000 men. The reasons for the rapid German victory have been debated often. The Allies, including Dutch and Belgian forces, had a clear advantage in number of army divisions, tanks, and armored vehicles. Airpower favored the Germans, but only because German air forces were concentrated in an aerial spearhead that pushed forward in coordination with the armored divisions on the ground. Military competence and strategic daring counted for something on the German side. The central problem for the Allies was the dispersal of their troops. Because French commander Maurice Gamelin had sent his reserve army northward, it could not plug the Ardennes gap. Aircraft were stationed all over France and Britain, but were not concentrated at the front; and the system of communications on the western side worked poorly. The argument that French soldiers lacked stomach for the fight because French society was in some sense "decadent" is difficult to prove. Their morale was poor because they sensed that they were poorly led. German victory in June 1940 had profound consequences. For the British and French, it was the worst possible outcome. France was defeated, its northern half as well as its Atlantic coast occupied by German forces. Britain was isolated from Continental Europe and had no prospect of reentering it to dislodge Adolf Hitler without the help of powerful allies (i.e., the United States and Soviet Union). France was now ruled by the authoritarian Marshal Philippe Pétain, who set up a new government center at Vichy, where his regime pursued policies that mimicked those of other Fascist states.

On June 10, 1940, Benito Mussolini's Italy declared war on Britain and France. Thus, a powerful enemy lay across Britain's main route in the Mediterranean to its eastern empire. Hitler was faced with the pleasing but unexpected prospect of German domination of Europe. On July 19, he announced before the Reichstag proposals for a European peace if Britain would accept the reality of German dominance and end hostilities. Churchill's government rejected it. British society braced itself for a possible invasion.

Hitler faced a critical dilemma in the summer of 1940. Successful beyond his expectations, he wanted to subordinate Britain in order to prepare for conflicts with the Soviet Union and the United States. When Britain refused to accept a German peace, Hitler ordered his forces to prepare to invade. The Luftwaffe (air force) was given the task of softening British resistance.

On July 31, a few days before the air attacks on Britain began in earnest, Adolf Hitler called his commanders together and told them that he had abandoned his and their hopes of invading the Soviet Union in the fall of 1940, and instead would begin that operation in the spring of 1941. German troops were sent into Romania and military arrangements were made with Finland since these two countries were to join Nazi Germany in invading the Soviet Union.

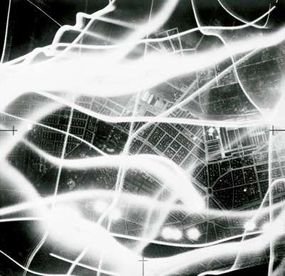

While the invasion of Britain (Operation Sealion) was being prepared, the Luftwaffe began its assault. This was the start of what would become known as the Battle of Britain. Waves of bombers, strongly supported by fighter aircraft, first attacked British air fields and sources of air supply. In September, they attacked the whole military and urban infrastructure within range of German fighters. The Germans' goal was to create conditions for landing an invasion force on the coast of southern England. The air battle was regarded as decisive only because the failure to eliminate Britain's Royal Air Force (RAF) would force the postponement of what the Germans considered a risky operation.

The defending British fighter force had difficulty preventing German bombing, but it was able to inflict high levels of attrition on the attacking force thanks to the first successful use of radar detection. From July to the end of October 1940, the RAF lost 915 aircraft while the Germans lost 1,733. The number of fighter pilots and fighter aircraft on the British side remained at roughly the same level as at the start of the battle, but German numbers declined. By mid-September, it was evident that the Luftwaffe was making little headway, and the first phase of the Battle of Britain was over.

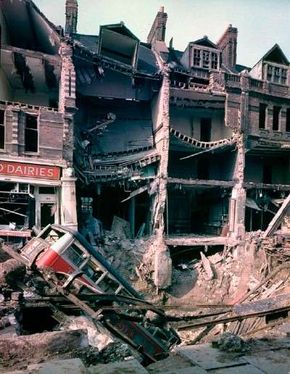

The second phase was more deadly and more prolonged. On September 17, Adolph Hitler postponed Sealion, and the Luftwaffe was given the task of knocking Britain out of the war by bombing alone. Heavy raids were directed at military and economic targets as well as urban areas, and civilian casualties were heavy. More than 40,000 British citizens were killed during the course of the "Blitz," which came to be directed at all major ports and industrial and commercial centers.

By December 1940, the German leadership expected Britain to surrender. "When will Churchill capitulate?" Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary. Bombing did produce widespread disruption and local panic, but at no point did the British government consider surrender. Gold and foreign exchange reserves were moved to Canada, and preparations were made for guerrilla activities in any portion of the country occupied by the Germans. The public was heartened by news of British victories in East Africa and Libya against Italian-led forces, and the knowledge that British bombers were regularly attacking German cities in return.

See the next section for a detailed timeline on the important World War II events that occurred during early April 1940.

To follow more major events of World War II, see:

Advertisement