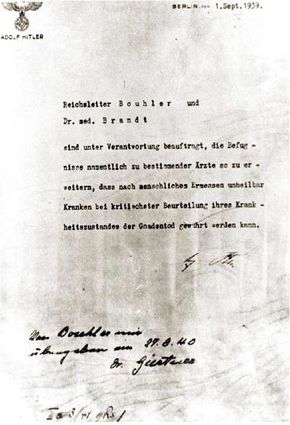

On September 1, 1939, just before Adolf Hitler's invasion of Poland that marked the beginning of World War II, Zygmunt Klukowski, a young Polish doctor, confided in his diary that everyone was talking about war. "Everybody," he continued, "is sure that we will win." The reality was startlingly different.

Nazi Germany's war with Poland, begun on September 1, was an uneven contest. Five German armies with 1.5 million men, 2,000 tanks, and 1,900 modern aircraft faced fewer than a million Polish troops with less than 500 aircraft and a small number of armored vehicles. In addition, German planning and technical support -- and German understanding of the importance of modern tactical airpower -- gave the aggressor great advantages.

Advertisement

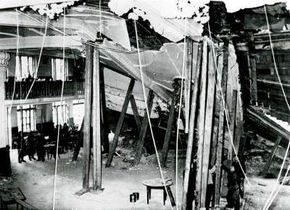

Within five days, German forces occupied all of the frontier zones. By September 7, forward units were only 25 miles from Warsaw, the Polish capital. Polish air forces were eliminated, and the Polish army was split and encircled. By September 17, the war was virtually over. Ten days later, after a devastating air assault, Warsaw surrendered. "We were not yet ready," wrote Dr. Klukowski two weeks later, "to discuss the causes of our defeat...This is a fact, but we just can't believe it."

This was the war Adolf Hitler had hoped for in 1939. But in addition to the localized conflict with Poland, the German invasion provoked a global conflict. Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany on September 3 when it became clear that negotiating a German withdrawal was hopeless. In Britain and France, the populations had braced themselves for war in the closing weeks of the summer. There was little popular enthusiasm for war, but a strong wave of anti-German and anti-Fascist sentiment produced a resigned recognition that Adolf Hitler would only stop if he was faced by force.

Almost immediately, the British and French empires (except for Ireland) joined the contest, turning it into a worldwide war, fought not only in Europe but across the oceans. German invasion also triggered Soviet Union intervention. The terms of the German-Soviet pact, signed in August 1939, gave Joseph Stalin a sphere of influence in eastern Poland. On September 17, once it was clear that Poland was close to defeat, Red Army units moved into Poland and met up with victorious German troops along a prearranged frontier. On September 28, the two dictatorships signed another treaty, which divided Poland between them.

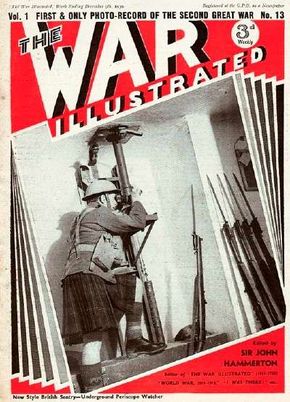

For the Western powers, this provoked fears of a totalitarian alliance against them. For Poland, dismemberment and harsh totalitarian rule was the reality. Britain and France did nothing to help their smaller ally. Their military staffs had drawn up a "war plan" during the summer of 1939 in which the loss of Poland was accepted as inevitable. The core of the plan was to blockade and contain Nazi Germany until the war of attrition forced the Germans to abandon the contest as they had done in 1918. Britain and France expected a war of at least three years. This explains why for the first six months of the war the Western states did very little. The lull was nicknamed the "Phony War" -- a war with no fighting.

A small amount of naval activity did occur, which gave citizens on both sides something to cheer about. In December 1939, Britain's Royal Navy so damaged the German pocket battleship Graf Spee that it was scuttled in the South Atlantic. Conversely, German submarines began to sink Allied merchant ships. On October 14, 1939, a German submarine managed to penetrate the defenses of the main British naval base at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, and there sank the battleship Royal Oak. The Germans bombed Polish citizens mercilessly, but for a while refrained from bombing cities in the West. The British only dropped leaflets on German cities.

The chief beneficiary of the war in Poland was the Soviet Union. Suffering almost no casualties, the Red Army took parts of Poland that had been seized by Russia and Austria back in the 18th century but returned to Poland after World War I. The region was integrated at once into the Soviet system.

More than one million Poles, those regarded as a threat to the Communist order, were deported to labor camps in the Soviet Union. The three Baltic States -- Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia -- had been assigned to the Soviet Union sphere by the August and September agreements. They were compelled by Soviet pressure to accept Soviet military garrisons and political advisers on their soil.

In the fall of 1939, the USSR demanded that the Finnish government cede some territory and allow bases on Finnish soil. Joseph Stalin had, in fact, already drawn up plans for a Communist Finland, and he expected the same response as the Baltic States had given.

Instead, Finland rejected the Soviet demands, and on November 30 Soviet forces invaded along the entire Finnish frontier. Finland's army of 200,000 mounted a spirited defense. Only after the mobilization of further Soviet forces in February 1940 did Finnish resistance wear down. Finland sought an armistice on March 6, and a week later it conceded all the territory and a base that had been originally demanded.

For Adolf Hitler, the Soviet advance in Eastern Europe and the spread of Communist influence were prices he had to pay for securing the German rear while Nazi Germany attacked Britain and France. But it was a dangerous situation. In October 1939, he hinted to his military staff that he would settle with the USSR as soon as he could. He hoped the West might seek terms, but when it became clear they were serious about war, he planned to attack the French front in November 1939. Poor weather prevented it, and Hitler reluctantly accepted a postponement until spring.

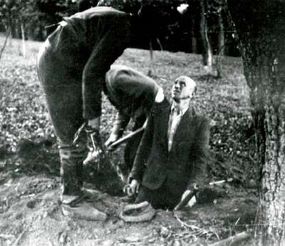

Urged forward by the German navy, Hitler decided to seize Norway and Denmark for the naval war against British trade supplies from America. What had begun as a war to extend German power in Eastern Europe had become an open and unpredictable conflict with the intervention of Britain and France. Only in Poland was the war really over. Dr. Klukowski watched in dismay as German troops looted shops and churches and forced Jews to give up their valuables and clean the streets. As he wrote late in 1939, "It is really hard to live in slavery."

Follow the events of the first week of World War II in early September 1939, on the next page.

To follow more major events of World War II, see:

Advertisement