Torture and Punishment During the Spanish Inquisition

Torture was used only to get a confession and wasn't meant to actually punish the accused heretic for his crimes. Some inquisitors used starvation, forced the accused to consume and hold vast quantities of water or other fluids, or heaped burning coals on parts of their body. But these methods didn't always work fast enough for their liking.

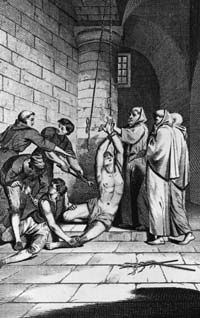

Strappado is a form of torture that began with the Medieval Inquisition. In one version, the hands of the accused were tied behind his back and the rope looped over a brace in the ceiling of the chamber or attached to a pulley. Then the subject was raised until he was hanging from his arms. This might cause the shoulders to pull out of their sockets. Sometimes, the torturers added a series of drops, jerking the subject up and down. Weights could be added to the ankles and feet to make the hanging even more painful.

Advertisement

The rack was another well-known torture method associated with inquisition. The subject had his hands and feet tied or chained to rollers at one or both ends of a wooden or metal frame. The torturer turned the rollers with a handle, which pulled the chains or ropes in increments and stretched the subject's joints, often until they dislocated. If the torturer continued turning the rollers, the accused's arms and legs could be torn off. Often, simply seeing someone else being tortured on the rack was enough to make another person confess.

While the accused heretics were on strappado or the rack, inquisitors often applied other torture devices to their bodies. These included heated metal pincers, thumbscrews, boots, or other devices designed to burn, pinch or otherwise mutilate their hands, feet or bodily orifices. Although mutilation was technically forbidden, in 1256, Pope Alexander IV decreed that inquisitors could clear each other from any wrongdoing that they might have done during torture sessions.

Inquisitors needed to extract a confession because they believed it was their duty to bring the accused back to the faith. A true confession resulted in the accused being forgiven, but he was usually still forced to absolve himself by performing penances, such as pilgrimages or wearing multiple, heavy crosses.

If the accused didn't confess, the inquisitors could sentence him to life imprisonment. Repeat offenders -- people who confessed, then retracted their confessions and publicly returned to their heretical ways -- could be "abandoned" to the "secular arm" [source: O'Brien]. Basically, it meant that although the inquisitors themselves didn't execute heretics, they could let other people do it.

Capital punishment did allow for burning at the stake. In some cases, accused heretics who had died before their final sentencing had their corpses or bones dug up, burned and cast out. The last inquisitorial act in Spain occurred in 1834, but all of the Inquisitions continued to have a lasting impact on Catholicism, Christianity and the world as a whole. In the next section, we'll see how the Inquisitions are viewed today.