Key Takeaways

- Ivar the Boneless is a character from the TV show "Vikings" known for his strategic prowess and physical disability.

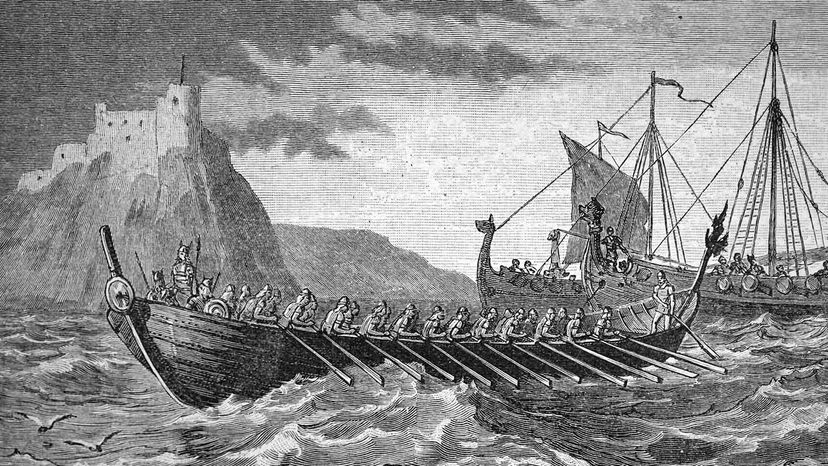

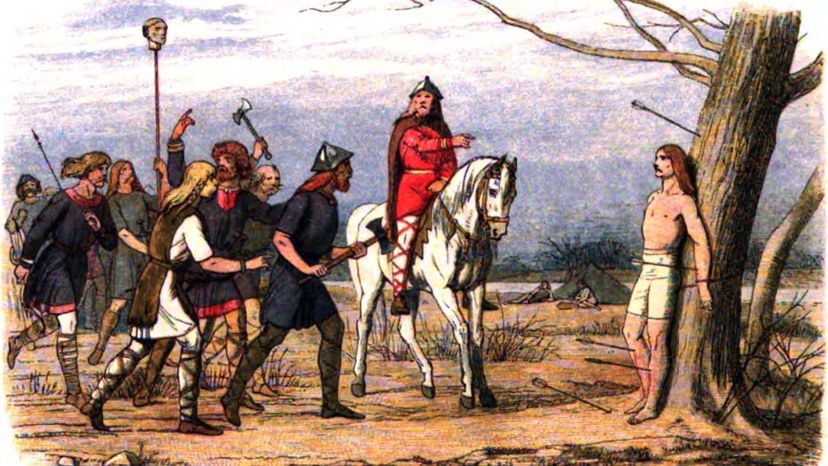

- The real Ivar was a Viking leader of the Great Heathen Army, but the origin of his nickname remains a mystery.

- Historical accounts and sagas offer conflicting information about Ivar's background and the reason behind his unusual title.

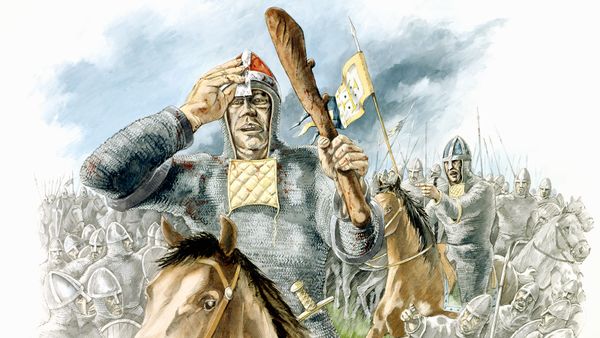

One of the breakout characters from "Vikings" — a History Channel drama that ended its six-season run in 2020 — is Ivar the Boneless. Played by Alex Høgh Andersen, he's an antihero fans love to loathe. The series depicts Ivar as a master tactician, a ruthless killer and a formidable foe on any battlefield.

All very impressive for a Viking who can barely walk. Andersen's Ivar has a lifelong medical condition that's rendered his legs useless. To get around, Ivar crawls, rides in chariots or hobbles on crutches. Despite this, he leads the "Great Heathen Army" in seasons four and five.

Advertisement

The showrunners didn't just make up Ivar the Boneless. He was a real person. And that wonderful, cryptic nickname? It first appears in texts written centuries after his death.

No one knows why folks called him "Ivar the Boneless." Maybe he was disabled, and maybe he wasn't. Like a lot of period dramas, the "Vikings" television show uses speculation and fantasy to plug gaps in our historical knowledge.

Advertisement