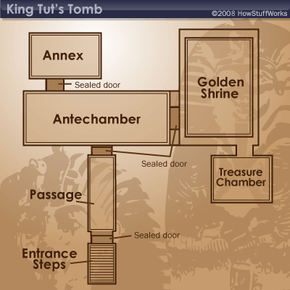

On Feb. 17, 1923, a crowd of about 20 invited guests gathered in an antechamber deep within the Valley of the Kings, an elite Egyptian city of the dead. Archaeologists and Egyptian dignitaries were there to view the unsealing of King Tutankhamen's burial chamber. While the tomb's outer rooms had already revealed a treasure trove of Egyptian art and furnishings, excavators were hoping to find something more: the undisturbed mummy of King Tut.

As Howard Carter, the expedition's chief archaeologist, cleared away the stone filling between the two rooms, the assembled audience watched in silence. After 10 drawn-out minutes of work, Carter created a small opening -- just large enough to peer into the chamber and see light bounce off the wall of a solid gold shrine.

Advertisement

While the treasure of Egypt's more prominent kings and queens had long since been looted, Tutankhamen's tomb lay protected for millennia by the debris of an ancient construction project. Although thieves had entered the tomb at least twice, they had never penetrated past the second shrine of the burial chamber.

Over the next several years, Carter would excavate the most famous cache of Egyptian treasure ever found. The burial chamber's nesting shrines, solid gold coffin and famous placid-faced mask would soon eclipse the splendor of the antechamber and annex.

But the excavation of the young king's tomb would also become famous for more ghoulish reasons. By April 1923, only two months after the chamber's unsealing, the project's financier, George Herbert, Lord Carnarvon, died of complications from a mosquito bite. Then his dog died. Then other people connected to the dig began to die under suspicious circumstances.

Rumors began to spread that Carnarvon and the others had stirred up the "mummy's curse," a Pharaonic hex dooming those who disturbed the rest of the dead kings and queens. An inscription supposedly carved on Tutankhamen's tomb warned that "Death will come on swift pinions to those who disturb the rest of the Pharaoh" [source: Ceram].

So is there any truth behind the curse? Can you really get sick from an ancient tomb? In the next section, we'll find out if the curse had any supernatural or scientific basis.

Advertisement