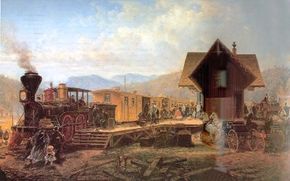

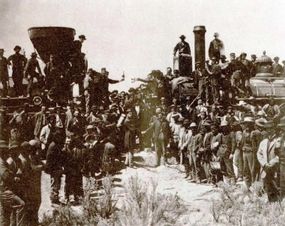

Three forces reshaped the United States between 1860 and the end of the century. First was the Civil War; second was the continuing tide of westward expansion; third was the American Industrial Revolution. Common to all was the railroad. It not only enabled the preservation of the Union, but also permitted the kind of rapid industrialization that made the United States a world power.

The Civil War was the defining event for nineteenth-century America, and railroads played an important role in the conflict. As the North industrialized rapidly between 1820 and 1860, railroads helped create --and prospered from -- the rise of factory production and diversified large-scale agriculture.

Advertisement

In the South, railroads played a marginal role in the cotton and tobacco economy. With little industry to support them, the railroads that did crisscross the inland South were lightly built, often poorly maintained, and generally inferior to those in the North. In the end, the North's industrial superiority -- epitomized by its superb railroad system -- enabled it to pummel the Confederacy into submission.

Both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis recognized the need for an effective railroad system in the war effort, and military men on both sides used railroads skillfully. The South, however, had neither the factories capable of building new locomotives in wartime nor the political will to forge the existing railroad network into a smoothly functioning system.

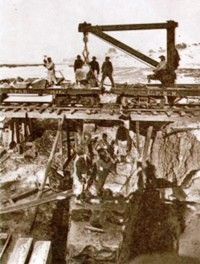

The North, on the other hand, quickly created the United States Military Railroad to expropriate and operate any railroad it needed. The Union Army appointed Daniel C. McCallum and Herman Haupt as ranking officers, giving them extraordinary powers to provide railroad support for northern troops.

Throughout the war, opposing forces recognized the tactical advantages of either controlling or destroying railroad supply lines. But it was not until Union General William Rosecrans found himself under siege at Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1863 that leaders discovered the true strategic value of railroads.

Over the objections of cabinet members and even some generals, Lincoln approved a daring plan to send two entire Army corps on a circuitous rail route to reinforce Rosecrans. Despite the short notice and complexity of the plan, railroad convoys carried 20,000 men, their full equipment, ten batteries with horses, and more than 100 cars of baggage and supplies 1,100 miles in just seven days (11 days from idea to execution).

Fifteen months later, 17,000 men made the reverse movement in an equally timely fashion on their way to complete the Union victory at Richmond, Virginia. War would never be the same again, for the railroad had proved to be a powerful military weapon as well as an agent of civilization.