The Bastille Falls and Louis Falters

The Bastille was an imposing relic of 14th-century warfare. In its prime, it was a medieval fortress; for centuries since, it had served as a prison and storehouse for gunpowder. But the Bastille was no ordinary prison: It quartered prisoners of the state who were convicted for crimes outside the realm of common law. The prison was shrouded in mystery, and legends abounded of the torture incurred by the men who resided within its eight stoic towers. The Bastille was symbolic of the monarchy in many ways -- it was a silent institution that answered to no one, yet doled out punishment as it saw fit.

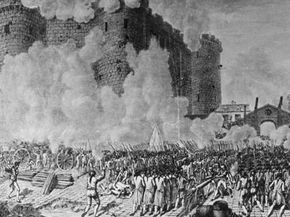

On the morning of July 14, the mob that marched to the Bastille was out for gunpowder and revenge. The first order of business was getting past the guards -- a pretty simple feat when you're armed with all manner of blades. Then, the crowd dispersed within the fortress, setting loose prisoners and gathering gunpowder. Two symbols of the coming French Revolution were brandished that day: the tricolour (the people's flag of red and blue divided by Bourbon white) and heads of the massacred on pikes. The march on the Bastille proved how ruthless and determined the French people were about their fight for freedom. Even after the last guard was killed and the last prisoner set free, the people stayed behind to dismantle the prison. The Bastille didn't exactly fall; rather, it was decimated from the top down in a laborious process unaided by modern wrecking balls and dynamite.

Advertisement

At Versailles, Louis could scarcely believe the news, but the National Assembly took it in stride. It was a victory for the people, and bloodshed was natural in revolution, wasn't it? But this was an important turning point for France. There was no longer any possibility for reform -- the movement had organically become a revolution.

The National Assembly quickly drafted the Declaration of the Rights of Man, in which Louis was essentially written out of authority. All men were declared equal, the class system a distant memory of France's feudal past. Ever a man of the people, Maximilien Robespierre authorized freedom of the press so that information could quickly be disseminated to the streets of Paris.

Freedom of the press paved the way for irresponsible journalism, however. Jean Paul Marat and Jacques Rene Hebert, respective authors of L'Ami du people and Le Pere Duchesne, were reckless propagandists. In many ways, their newspapers kept stride with the mounting tension, but they also stoked the fires of revolution. What Robespierre did for the Estates General and the National Assembly, Marat and Hebert did for the people of France. Their words excited the third estate, confirming in their minds that the revolution was a natural and just movement. But with increasingly vulgar language and paranoid indictments, the newspapers were less credible sources of information than they were death warrants for the clergy and nobility.

When Marat printed that the king and his courtiers had desecrated the tricolour at a recent party at Versailles, it unleashed another frenzy. Marat urged the people to take up arms and fight back -- and he pointed to the increasing number of Louis' troops around the city as evidence that the monarchy was preparing to wage its own retaliation against the revolution.