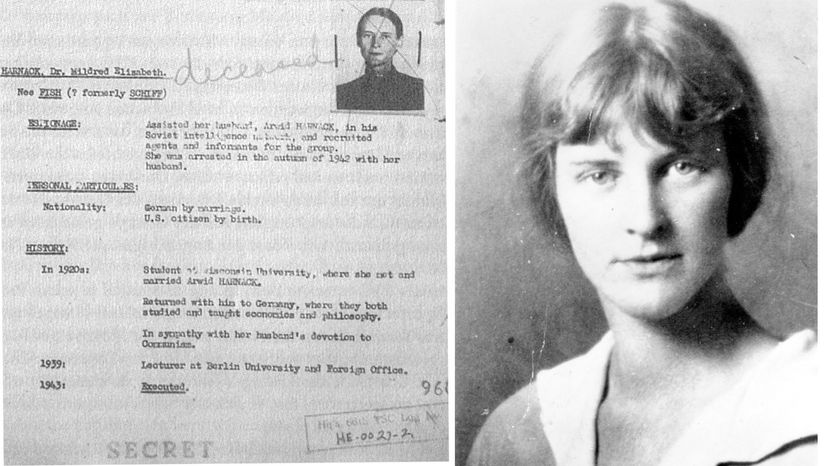

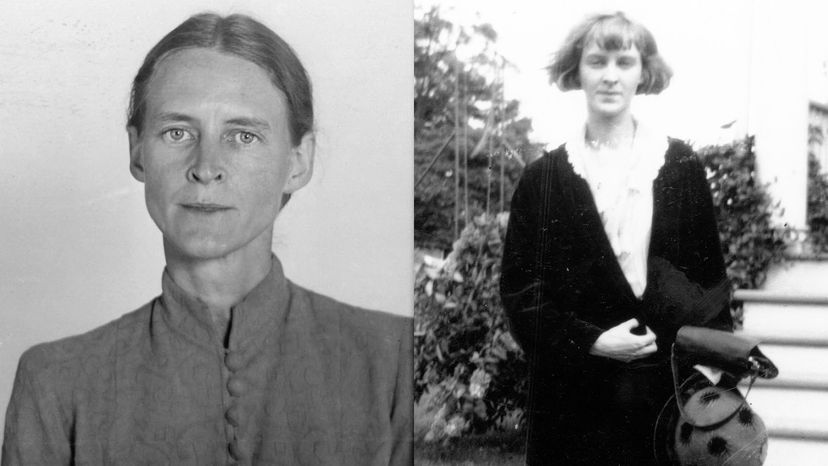

If you've never heard of Mildred Harnack that's about to change. By any measure, the free-thinking young woman from Wisconsin is an American hero.

During World War II, Mildred and her German husband Arvid lived in Berlin, where she became the only American — male or female — to serve as a leader in the underground German resistance against Adolf Hitler.

Advertisement

Mildred paid the ultimate price for her brave opposition to the Nazis. She was sentenced to six years of hard labor for the crimes of treason and espionage, but ultimately Hitler personally ordered her to death in 1943.

But instead of being hailed as a freedom fighter back home, Mildred and her co-conspirators were falsely painted as "communist spies" working for Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. Mildred's own family burned her letters for fear of being labeled as communist sympathizers.

Eighty years after her execution, Mildred's remarkable true story is being told, thanks in large part to her great-great-niece, author Rebecca Donner.

We spoke with Donner about her award-winning biography of Harnack, "All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days," to learn how a literature professor from Milwaukee dared to stand up to Hitler and the Third Reich.

Advertisement