Three years later, Great Britain and the United States reached an agreement about the Pacific Northwest's political future. Under the Oregon Treaty of 1846, nearly all of the disputed lands below the 49th parallel were handed over to the U.S. (Notably, British Canada retained all of Vancouver Island.)

An act of Congress in 1850 recognized most of the land claims that were made under Oregon's provisional government. The policy of doling out free land to northwestern migrants continued until 1854, when a fee of $1.25 per acre was imposed — and a cap of 320 total acres (i.e.: 129.4 hectares) per new claim was enforced.

Those terms were attractive enough to keep the hopeful settlers streaming in. Their preferred mode of transportation was a covered wagon. Pulled by mules, horses or oxen, these consisted of rectangular, box-shaped "beds" with removable canvas covers. A typical wagon in those days could carry loads of 1,600 to 2,000 pounds (725 to 907 kilograms).

"People packed various things, but what they arrived with was a different matter," Wolf says. Littering was rampant along the Oregon Trail: Travelers left everything from old furniture to dinnerware scattered across the American countryside.

"With limited space on the wagons, they had to have some food, repair tools, spare parts and maybe some family heirlooms," Wolf explains. "With very [few] settlements/forts along the way, they had make sure they had enough supplies."

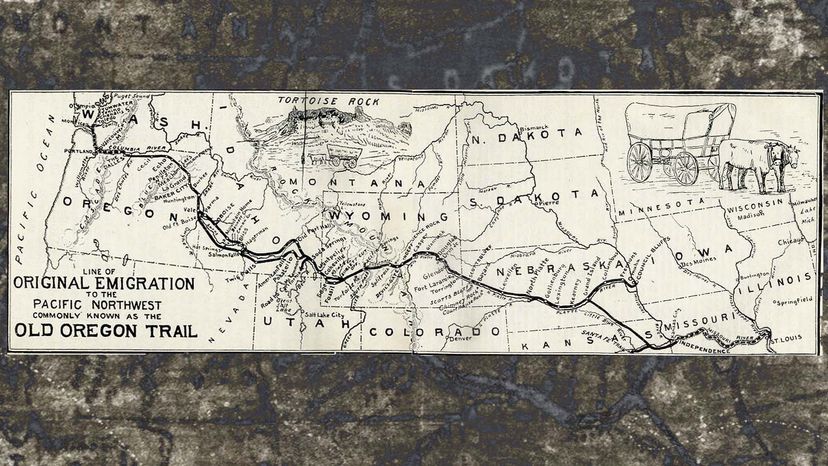

Most families traveled in wagon trains, organized caravans that sometimes contained more than 1,000 individual settlers. Mind you, these didn't always follow the exact same course. On their way through Missouri, Nebraska, Wyoming and other states, wagon train pathways covered vast expanses of land. "The trail got very wide," notes Wolf.

And it was full of graves. Conservatively, about 4 to 6 percent of all the emigrants who took the Oregon Trail died along the way. Many a wagon train was devastated by cholera, dysentery and other diseases. "You also had death from fording dangerous rivers, snake bites [and] accidents... like getting run over," Wolf says.

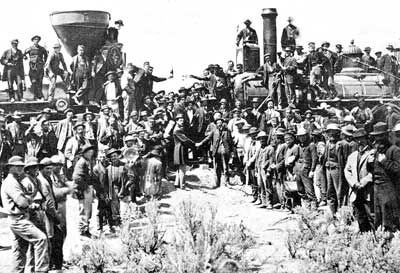

Following the completion of America's first Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, the Oregon Trail's heyday came to an end — though some families were still using it in the 1890s. Although its golden age is long past, there's no denying that this beautiful but punishing route changed America forever.