Since the Middle Ages, France had been divided into a three-class system. The clergy made up the first class, the nobility made up the second and the peasantry the third. There was no room for social climbing: Kings gave birth to kings, paupers gave birth to paupers. For centuries, the Old Regime held all the power in France. The nobility and clergy represented only 3 percent of the French population, but their minds conceived of the policies that governed the entire country. This system was rigid and uncompromising, but no one paused to consider -- or dared to say -- that it was unfair.

By the 18th century, the Enlightenment was dawning. Philosophers like Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau advocated for equality and reason. They asked why people put their faith in political and religious leaders who disregarded their needs. In salons, the wealthy members of Parisian society debated these issues. Their eyes were on the American colonies, where the Americans had gone to war to claim their rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. (Meanwhile, Thomas Jefferson, who'd described these principles in the Declaration of Independence, had also declared that if France's queen Marie Antoinette had been shut up in a convent, France could have avoided the revolution [source: Smithsonian].) While the French nobles pondered the unfairness of the universe, peasants went hungry in the streets of Paris and in the outlying provinces.

Advertisement

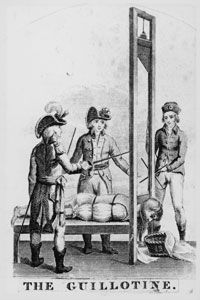

One of the medieval precedents that persisted in the 18th century was brutal execution. Criminals were burned, drowned, tortured and maimed -- all under the consenting eyes of the Old Regime. However, the French nobility were entitled to execution by decapitation. While it seems a particularly grisly way to die, decapitation is relatively swift and straightforward, a real gentleman's death. When Dr. Joseph Ignace Guillotin joined France's Constituent Assembly in 1789, he proposed that all capital criminals sentenced to death be decapitated. Guillotin advocated for the creation of a decapitation device like the ones used in England, Germany, Italy and Scotland. The device was prototyped in Germany by the secretary of the Academy of Surgeons, who ensured that it was humane. By 1791, after a trial period during which the device sliced through countless cadavers, it was appointed France's national death-sentence machine. It was called the guillotine.

The guillotine was just a small part of an enlightened equal rights movement sweeping through France. While Guillotin advocated for equality in death, the French people were fighting for equality in life. And ironically enough, the guillotine would be misappropriated in this struggle. It became a tool of terrorism in the French Revolution as the undiscerning blade silenced nobles, radicals and ordinary citizens.

It's a question for the ages: What could turn a group of loyal subjects into a bloodthirsty mob? The movement that began as a reformation steadily devolved -- or evolved, depending on whom you ask -- into a full-fledged revolution. The French Revolution lasted for 10 years, from 1789 to 1799. But trouble began brewing in France years before dissident political factions went on witch hunts for counter-revolutionaries.

So did the revolution actually accomplish anything it set out to? Was it just about brotherhood and bread, or were there darker forces at work? The events of the French Revolution and the motley crew of characters responsible for them are as varied, complicated and painstakingly interwoven as a juicy soap opera plotline. We'll begin at the seat of power, in Versailles.