Estates General Resurrected

Louis was aware of his powerlessness. He exacted authority through financial initiatives, but these ill-advised policies only burdened the poor and pardoned the rich. His deregulation of grain may have been the very worst of these new policies. The cost of bread increased more than tenfold in some instances, and the people could no longer afford the mainstay of their diet. Mobs lynched bakers and looted precious loaves from their shops. While the court of Versailles ate to excess, the people of France went hungry in the streets.

Royal advisers prodded Louis to elect a finance minister. Obligingly, he appointed Jacques Necker in 1789. Necker was a pragmatic Enlightenment thinker who set out to reform government finances so that they'd serve the people. Necker's boldest move was calling a meeting of the Estates General, a legislative body made up of deputies (or representatives) from each of the three estates. The Estates General hadn't been assembled since 1614.

Advertisement

Though 175 years had passed since its last meeting, not much had changed in the Estates General. Power still rested with the first and second estates: the clergy and the nobility. The deputies' votes carried equal weight, but the first and second estate represented a sliver of a fraction of the French population. Because the first and second estate usually voted the same way on issues, the upper classes benefited from governmental policies while the third estate shouldered the burden of the wealthy.

The French wanted the justice of a three-chambered parliament to solve this imbalance (similar to how the American colonists rallied for no taxation without representation). The people began clamoring for identity. Pamphlets and newspapers flooded the streets of Paris as the people tried to define themselves in terms of class. In January 1789, theorist Emmanuel Joseph Sieyes put it like this: "[W]hat is the Third Estate? Everything; but an everything shackled and oppressed. What would it be without the privileged order? Everything, but an everything free and flourishing. Nothing can succeed without it, everything would be infinitely better without the others" [source: Modern History Sourcebook].

A lawyer named Maximilien Robespierre was less poetic than Sieyes, but he was an active, incendiary speaker. In early May of 1789, Robespierre went to Versailles to serve as a deputy at the Estates General. He was a true representative of the people; from the beginning, he incited unrest among the staid deputies when he proclaimed that all estates should pay taxes. Robespierre's perspective was guided by Enlightenment logic, and it quickly gathered popularity as well as derisive ire.

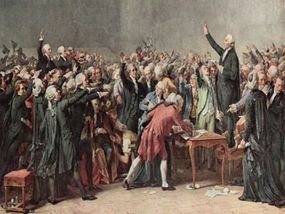

Nearly two months of heated debate fueled the long-dormant Estates General, and the members of the third estate even won over some members of the clergy and nobility to their cause. But discussion was silenced on June 20, 1789, when members of the first and second estates bolted the doors of the Estates General shut. Undaunted, deputies found an unoccupied indoor tennis court and reconvened there. They identified themselves as the National Assembly and passionately swore to write a constitution for the people of France, in what became known as the Tennis Court Oath.

During the early days of the National Assembly, there was a shred of hope that Louis might endorse this constitution. But when 30,000 of the king's troops were positioned around Paris, the people realized that reform wouldn't be won through politicos' promises and hopeful treatises. They responded by creating a homespun militia. The people broke into armories and swept the stores clean of firearms.

Then, Louis made the fateful decision to dismiss Necker from his position as minister of finance. The people viewed this as a direct retaliation to their cause. There was no mobilization of troops, no grand pronouncement of attack. On July 14, sheer chaos broke out in the streets of Paris, and the people headed for the Bastille.