On September 18, 1931, a group of Japanese soldiers stationed in the northern Chinese province of Manchuria, masquerading as Chinese bandits, blew up a few feet of the Japanese-controlled South Manchurian Railway. The clumsily orchestrated incident was used as a pretext to launch an attack by the Kwantung Army (Japan's field army in China), which aimed to occupy the whole of the province and bring its rich resources under Japanese control. This was the start of a decade of escalating violence that would culminate in the German assault on Poland and the start of World War II.

Within months of the Japanese seizure of Manchuria, the fragile international order of the 1920s was in tatters. The League of Nations did little to protect China from Japanese aggression, and in February 1933 Japan left the League altogether. Japanese statesmen and military leaders had grown frustrated by an international political and economic order that they thought gave them a second-rate status. The global economic slump hit Japan hard, and its goods were excluded from some markets. The world order seemed set to benefit big imperial powers rather than what were called the "have not" powers -- those with poor supplies of raw materials, a modest colonial empire, and an alleged imbalance between population and territory.

Advertisement

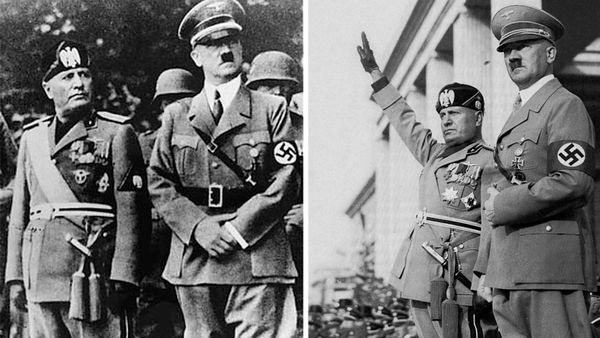

Japan was only the first of the powers that acted in defiance of the existing order. Italian dictator Benito Mussolini wanted an international revolution by what he called the "proletarian states" against the "plutocratic powers," namely Britain, France, and the United States. From 1932 he hatched plans to conquer the independent African state of Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia), and in October 1935 Italian forces invaded the kingdom, which they conquered by the following May. This time the League imposed half-hearted economic sanctions. In December 1937, Italy also left the League.

For the long-term stability of the international order, the most dangerous development was the rise to power in Nazi Germany of Adolf Hitler and his movement of fanatical nationalists. The National Socialist Party rejected the Versailles settlement, repudiated the international economy (which they associated with Jewish financial power), and called for the rearmament of Nazi Germany to conquer the globe. On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor. Over the next six years, he was the driving force behind public repudiation of the peace settlement and the expansion of German political and economic influence over Europe.

Adolf Hitler was convinced that Nazi Germany was a "have not" power. He adopted the popular idea of Lebensraum (living space) as a justification for German territorial expansion and the seizure of new economic resources. He also was convinced that Nazi Germany represented a superior culture and was destined to dominate lesser races. He attributed Nazi Germany's current weakness to the malign influence of international Jews, whom he felt had stifled German economic growth, enfeebled the German people, and undermined German cultural heritage. This potent mix of prejudices and grievances became the basis of German foreign policy.

In early 1935, Adolf Hitler publicly announced a secret rearmament that had been going on since the late 1920s. In March 1936, he ordered German forces to remilitarize the Rhineland region in defiance of the Treaty of Locarno. On November 5, 1937, he announced to his military commanders his intention of uniting Austria with Nazi Germany and destroying the Czechoslovakian state (set up in 1919) as the preliminary to a wider war. On March 12, 1938, German forces entered Vienna amid scenes of hysterical enthusiasm. The rest of the world did nothing, as it had done nothing over Manchuria and Abyssinia.

By the mid-1930s, a gulf separated the three revisionist powers -- Nazi Germany, Italy, and Japan -- from the major democracies that had dominated the world order in the 1920s. In November 1936, Nazi Germany and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, which was directed at the international struggle against communism; a year later, Benito Mussolini signed up to it as well.

These three nations wanted to alert the Western powers that they saw themselves as a Fascist bloc increasingly opposed not just to communism, but to Western liberal democracy as well. This division was made explicit with the outbreak of civil war in Spain in July 1936. Nazi Germany and Italy both committed forces to help the nationalist rebels under General Francisco Franco. Britain and France led a noninterventionist movement that weakened the cause of the legitimate republican government and exposed the weakness and uncertainty of the West.

For Britain, France, and the United States, the main architects of the post-WWI international order, it was difficult to find ways of containing the sudden crisis. None of the three wanted to risk a major war so soon after the last, but none of them wanted to let the world order slide into chaos. There were powerful pressures against an active foreign policy. The British and French empires were menaced by anticolonial nationalism in India, Indochina, the Middle East, and Africa.

In Palestine, Britain was forced to deploy troops in large numbers to keep the peace between the Arab majority and the Jewish population, which had been promised a Jewish homeland at the end of World War I. In India, the so-called jewel in Britain's imperial crown, popular nationalism -- inspired by the apostle of nonviolent resistance, Mohandas Gandhi -- forced the British government to grant limited self-government with the India Act of 1935. The United States had abandoned the settlement it had helped write.

Even if British and French leaders had taken a more active line, powerful domestic lobbies pushed for pacifism. When a center-left government was elected in France in 1936 under the slogan of the Popular Front, a million Frenchmen marched through Paris demanding peace. In 1934 British citizens founded the Peace Pledge Union, which over the next five years became a mass movement that campaigned against war. Not until Nazi Germany seemed a very real threat in 1939 did public opinion swing more clearly in favor of confronting fascism by violent means.

A second major issue was the attitude of the two potential economic and military giants of the 1930s, the United States and the USSR. Only a decade later, these two states would be the world's superpowers. Yet in the 1930s, they played a more limited role, and their military power was more potential than real. In the United States, the impact of the Great Depression after 1929 encouraged a mood of isolationism. When Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president in 1932, he promised a "New Deal" for America's impoverished population. His priority was to heal America first and to avoid any international policies that compromised that priority.

Congress adopted the provisional Neutrality Law in 1935, then passed permanent legislation in 1937 designed to prevent the United States from giving money, economic aid, or arms to any combatant state. Though American statesmen remained anxious about Japanese ambitions in the Pacific, and sympathized instinctively with Chinese resistance, Americans did nothing to inhibit Japanese aggression. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was personally hostile to Nazi Germany and to fascism, but he felt too constrained by the economic crisis at home to risk persuading the American people that involvement in European affairs was necessary for American security.

The Soviet Union was an unknown and potentially dangerous power. Though the Communist threat was just brewing by the 1930s, Western states were aware that Communists were committed to the long-term subversion of the West's social and political systems. In the 1930s, the USSR began a program of massive industrialization and rearmament, which made Russia the third largest industrial economy by 1939 and, on paper, the world's biggest military power. Yet Soviet leader Joseph Stalin concentrated on building up the new Soviet system and defeating the remaining domestic "enemies" of the revolution rather than act more forcefully in international affairs. The Soviets did not want war, and hoped to minimize its risks.

In September 1934, the Soviet Union was admitted to the League. However, Communists distrusted the democratic leaders as much as the Fascists, seeing both as varieties of capitalist politics. Britain and France were wary throughout the 1930s of any commitment to the Soviet Union. Although a pact of mutual assistance was signed between France and the USSR in May 1935, it was never turned into a military alliance.

The result of all these many pressures was a confused Anglo-French response -- a mix of inaction, mild protest, and concession that is normally described by the term "appeasement." Efforts were made to find ways to keep Nazi Germany, Italy, and Japan within the existing power structure. In 1935 Britain and Germany signed the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, which legitimized German naval rearmament, although it was broken by Nazi Germany the year it was signed. Neither Britain nor France risked confronting the Fascist states regarding intervention in Spain. Japan was left alone in the Far East, with only minimal aid provided to China. Nevertheless, both Britain and France realized that war was a strong possibility, and fear of war was a central element in the popular political culture of these nations in the 1930s. From 1936 both states began a program of rearmament.

Evidence of Western hesitancy encouraged the revisionist powers to press on. Japan began full-scale war with China in 1937 and conquered much of China's eastern seaboard by 1938. In Europe, Adolf Hitler ordered his generals in May 1938 to plan an autumn war against Czechoslovakia on the pretext of freeing the German-speaking peoples of the Sudetenland from Czech domination. But when German pressure reached a peak in the summer, Britain and France intervened. Neville Chamberlain, Britain's prime minister, flew to Nazi Germany to meet Adolf Hitler and broker a deal. The result was the Munich Agreement signed on September 30, 1938. The Sudetenland was given to Nazi Germany, but war was averted. In addition, Adolf Hitler was forced to back down from the destruction of Czech independence, which had been his aim.

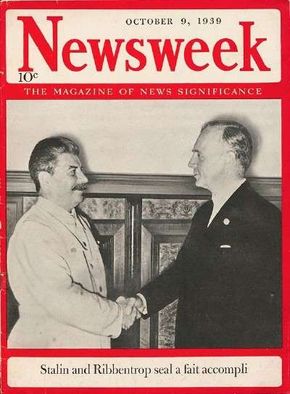

Unhappy that he had not gone to war with the Czechs in 1938, Adolf Hitler added Britain and France to his list of potential enemies. But he turned first to the east, annexing a large part of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, before insisting that Lithuania and Poland cede Memel and Danzig and come into the German orbit. Only Poland refused to subordinate itself to Berlin, so Adolf Hitler decided to attack that country either by itself or alongside France and Britain if those states intervened. Under these circumstances, he responded to soundings from Moscow that he had earlier rejected. In a secret agreement with the Soviet Union, he agreed to partition Eastern Europe on the assumption that he would conquer it all after defeating the Western powers.

In the winter of 1938-1939, the British and French decided that if the Germans attacked any country that defended itself, they would join in its defense. In the hope that this might deter Nazi Germany, they publicly promised to defend Romania, Poland, and Greece, but Nazi Germany went ahead anyway.

On August 31, despite mounting evidence of Western firmness, Adolf Hitler ordered the campaign to begin the next day. Heinrich Himmler, his security chief, repeated what Japanese soldiers had done in Manchuria in 1931 by staging a fake act of provocation. In alleged retaliation, German forces advanced on a broad front into Poland on the morning of September 1, 1939.

See the next section for a detailed timeline on the important World War II events that occurred during 1931-1933.

For additional information about World War II, see: