Western Railroad Labor

Because of a labor shortage in the West, the Central Pacific hired Chinese immigrants as laborers, finding them to be such skilled, diligent, and efficient railroad builders that the CP began recruiting workers from southern China. At one point, more than 14,000 men were at work on the CP -- mostly Chinese, along with a handful of Irish- and American-born railroaders. They battled incredible winter snows, granite that yielded only grudgingly to black powder, and some of the roughest terrain on the continent.

On the Union Pacific, Irish and other European immigrants joined former Confederates, Union veterans, and anyone else who could work from sunup to sundown for a dollar or two per day. The men ate beef, bread, and pie; liquids were limited to bad whiskey, boiled coffee, and whatever water was at hand. Ferocious summer heat, terrific storms, and sporadic Indian attacks made hard physical work even worse.

Advertisement

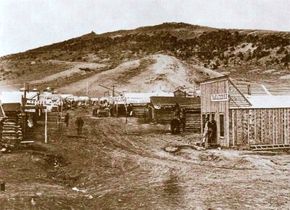

As the tracks advanced farther away from civilization, portable towns dubbed "Hell on Wheels" followed the UP railhead, providing women, gambling, cheap liquor, and the roughest amenities. Some, like Cheyenne, Wyoming, became permanent towns, transforming themselves into respectable communities. Others disappeared without a trace.

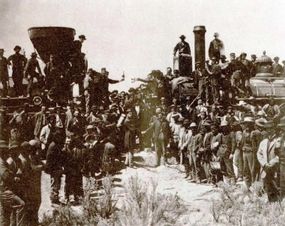

The ceremony marking the connection of the two railroads at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10, 1869, was small and simple. The Union Pacific had built 1,086 miles of main line; the Central Pacific, 690 miles. After prayers, speeches, and placement of the last rails, dignitaries took turns gently tapping gold and silver spikes into a pre-drilled laurel tie. The estimated 600 men and women gathered at the site cheered as the telegraph flashed the news to an anxiously waiting country: Done! Across the United States, Americans cheered what they regarded as the most important project of their lifetimes -- and a sure sign of the prosperity to come.